Rising Violence in Arab Society and Community Resilience Initiatives

Knesset Committee Testimony

The Abraham Initiatives’ Semi-Annual Monitoring Report for January–June 2025 presented a deeply concerning picture of violence within Arab society in Israel. The report documented 128 Arab citizens killed in the first half of 2025, a number that has since risen to 146. This marks a sharp increase compared to 109 fatalities in the same period of 2024 and 111 in 2023, which was already a peak year.

At a Knesset National Security Committee session, Lama Yassin, Director of the Mixed Cities Initiative at The Abraham Initiatives, warned of an escalation in extremist attacks against Palestinians:

“In recent months, we have witnessed an unprecedented and unacceptable escalation in violence against the Arab population... It reached a new low when Jewish citizens applauded the death of four Arab women in Tamra during the war with Iran.”

She highlighted violent incidents targeting Knesset members, bus drivers, and journalists, as well as hostile online commentary celebrating the suffering of Arab communities. Yassin stressed the urgent need for Israeli leadership to address these fundamental threats to social cohesion.

Strengthening Bedouin Communities through Security Training

Amid these challenges, The Abraham Initiatives’ Safe Communities Initiative is showing promising results. Over 671 graduates (400 women, 271 men) from 23 courses across 15 Bedouin towns have now completed Personal Security Courses.

Impact data reveals significant progress:

Reporting of shooting incidents to police rose from 13% to 90%.

Readiness to take action against violence increased from 30% to 94%.

Understanding of emergency response protocols improved from 14% to 90%.

A campaign promoting security and resilience reached 1.3 million views on social media.

These efforts demonstrate how locally driven initiatives can enhance safety, empower communities, and foster resilience—particularly among women and youth.

Intercommunal Healthcare Forum

The second meeting of the Healthcare Expert Forum, co-hosted by The Abraham Initiatives and the Galilee Society, convened Jewish and Arab professionals to share best practices for maintaining workplace solidarity during crises. Key recommendations included:

Assigning designated personnel to manage relations.

Ensuring strong, consistent leadership messaging.

Establishing protocols to address offensive comments and protect Arab staff.

Creating safe spaces for dialogue.

Managing organizational messaging during public events.

Defending Democratic Representation

In a related development, a Knesset proposal to remove MK Ayman Odeh, leader of the Arab-majority Hadash-Ta’al Party, was defeated. The attempt drew widespread criticism from civil society organizations, who argued it was an unprecedented assault on democratic representation. Mobilization by advocacy groups helped ensure the failure of this measure, safeguarding the political voice of Arab citizens.

The data and testimony presented this month reveal the severity of violence facing Arab citizens, the persistence of extremist attacks, and the urgent need for government accountability. At the same time, the progress achieved through grassroots initiatives such as the Safe Communities program underscores the power of resilience, community-led security, and cross-communal cooperation to drive meaningful change.

Learn more here: https://abrahaminitiatives.org

Our Genocide: B’Tselem’s Urgent Call to Halt the Destruction of Gaza

We share with you an important and deeply troubling new report released this month by B’Tselem, the Israeli human rights organization. The report, titled Our Genocide, documents what the authors conclude is an ongoing genocide committed by Israel against the Palestinian people, particularly in the Gaza Strip, since October 2023.

What the Report Finds

The 86-page document outlines in detail the destruction of Palestinian life across Gaza, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and within Israel itself. It draws on eyewitness testimony, field research, humanitarian data, and international law.

Mass Killings & Trauma: By mid-July 2025, more than 58,000 Palestinians in Gaza had been killed, with nearly 140,000 wounded. Women, children, and the elderly make up a significant proportion of victims. Life expectancy has collapsed; for men, it has dropped by over 50% since October 2023.

Destruction of Living Conditions: Starvation, collapse of healthcare, destruction of housing, and deliberate targeting of water and electricity infrastructure have created catastrophic conditions. The report notes starvation is being used as a method of warfare, with deaths mounting daily.

Forced Displacement: Millions have been driven from their homes in Gaza and the West Bank. “Safe zones” have been repeatedly bombed, including al-Mawasi, where 90 were killed and 300 injured in one strike.

Psychological & Cultural Assault: Entire generations, particularly children, are suffering extreme trauma. Education, religious sites, family structures, and press freedom have been systematically undermined.

Prison Camps & Torture: Thousands of Palestinians are detained without trial in prisons described as “torture camps.”

Incitement & Dehumanization: The report compiles statements from senior Israeli leaders and soldiers reflecting genocidal intent, where all of Gaza’s population is seen as complicit or disposable.

Genocide as a Process

The report stresses that genocide is not only about mass killings. It is a process — one rooted in decades of apartheid policies, ethnic cleansing, and systemic dehumanization. The Hamas-led attack of 7 October 2023, the report argues, became the triggering event that enabled the Israeli government to escalate from repression to outright destruction.

A Call to Action

B’Tselem, whose name means “in the image [of God],” has for 35 years documented human rights violations in Israel and Palestine. With this report, they call on both Israeli society and the international community to urgently act to stop the genocide, protect Palestinian lives, and prevent its further spread beyond Gaza.

“We all live under a discriminatory apartheid regime that classifies some of us as privileged subjects simply because we are Jewish, and others as undeserving of any protection simply because we are Palestinian. Together, we fight for the right we all have to live between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River without discrimination, violent repression and annihilation.” — Our Genocide, B’Tselem

Read the full report here: Our Genocide (B’Tselem, July 2025).

Remembering Awdeh Hathaleen: A Voice for Peace Silenced

We share the deeply painful news that Awdeh Hathaleen, a beloved teacher, community leader, and advocate for nonviolent resistance in Masafer Yatta, has been killed. Awdeh, known for his dedication to peace and his tireless efforts on behalf of his community, was shot dead by a settler outside the Palestinian village of Umm al-Khair.

Just hours before his death, Awdeh sent an urgent message about settlers working behind homes in his village, attempting to cut the main water pipe and establish caravans. His last words underscored his lifelong commitment to protecting his community:

“We need everyone who can make something to act… if they cut the pipe the community here will literally be without any drop of water.”

A Life Cut Short by Violence

Witness accounts detail that settlers arrived with bulldozers, destroying olive trees and injuring residents. During this attack, extremist settler Yinon Levi fired his weapon, killing Awdeh. Levi has previously been sanctioned by the United States for violence against Palestinians but was freed from such restrictions when sanctions were revoked in early 2025.

For years, Awdeh welcomed visitors, including members of Congress and civil society leaders, into his community, showing the daily challenges faced by Palestinians in the South Hebron Hills. His death is both a personal tragedy for those who knew him and a stark symbol of the unchecked settler violence afflicting Palestinian communities.

J Street’s Response

J Street issued a strong statement mourning Awdeh’s death and calling for accountability:

Urging Israel to investigate and bring perpetrators to justice.

Calling on the U.S. government to press Israel to ensure accountability.

Renewing advocacy for the West Bank Violence Prevention Act (H.R.3045), introduced in Congress to codify sanctions against violent settlers and deter further attacks.

Read the full statement here: J Street Statement on Awdeh Hathaleen

A Call to Action

Awdeh’s death highlights the urgent need to confront settler violence and the broader structures that enable it. By supporting legislation like the West Bank Violence Prevention Act and demanding accountability, there is a chance to honor Awdeh’s legacy and protect others from the same fate.

Petitions are circulating to encourage Members of Congress to support the bill. Once signed, participants will receive instructions on how to contact their representatives.

Awdeh Hathaleen will be remembered as a peace-loving leader whose voice called for dignity, justice, and hope. May his memory serve as a blessing—and as a call to action.

Emergency Discussion: The Starvation of Gaza

Black Flag in Academia is convening an urgent online event to address the worsening humanitarian crisis in Gaza, where starvation is being used as a weapon of war.

Since 2007, Israel has controlled the availability of foodstuffs in Gaza through a blockade. Following the events of October 7, 2023, this control has intensified, raising alarm that starvation is being deployed as a method of warfare against Palestinians. While Gaza has experienced food scarcity during the past 21 months, the situation has deteriorated sharply in recent days. Since July 21, 2025, at least 54 individuals have died from starvation. Analysts and health professionals stress that this catastrophe is entirely man-made and the direct consequence of Israeli policy.

Event Details

Date: Monday, July 28, 2025

Time: 21:00 Israel/Palestine | 20:00 CET | 2:00 PM EDT

Format: Live Zoom discussion and broadcast

Access link: Join Zoom Meeting

Speakers

Dr. Ezzideen Shehab, Al-Rahma Medical Center

Prof. Roni Strier, Haifa University

Tamar Luster, Tel Aviv University

Prof. Alex de Waal, World Peace Foundation and Tufts University

Moderator:

Dr. Fatina Abreek-Zubeidat, Tel Aviv University

Discussion Focus

This emergency panel will explore:

The immediate and long-term impacts of starvation in Gaza

The legal frameworks surrounding starvation as a method of warfare

The role of international actors and civil society in preventing further catastrophe

Concrete steps that can be taken to stop this man-made crisis

This event offers an opportunity to hear directly from medical experts, academics, and policy specialists about one of the gravest humanitarian emergencies of our time.

Announcing the 2025 FASPE Fellows

FASPE (Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics) has announced the 2025 cohort of Fellows. Since its founding in 2010, FASPE has granted nearly 85 fellowships annually across six professional fields—Business, Clergy & Religious Leadership, Design & Technology, Journalism, Law, and Medicine. The program emphasizes ethical leadership and responsibility, recognizing the impact that professionals hold in shaping society.

Each fellowship convenes in Germany and Poland, where participants engage in rigorous study of professional ethics through historical and contemporary lenses. This approach underscores FASPE’s mission: to explore how influence can be exercised responsibly in professions that profoundly affect civic life.

This year’s Fellows will join a network of more than 900 alumni worldwide who are committed to ethical leadership and to addressing the moral challenges of their respective fields.

Business Fellows

Among those selected are professionals and students from institutions such as Harvard Business School, MIT Sloan, Columbia Business School, Duke Fuqua, and Boston Consulting Group. Their work spans consultancy, global supply chains, and assistive technology.

Clergy & Religious Leadership Fellows

The clergy cohort brings together leaders and emerging voices from across Christian denominations and global institutions including Yale Divinity School, Abilene Christian University, Free University of Berlin, and Santa Barbara’s New Beginnings.

Design & Technology Fellows

This group features professionals from leading technology firms including Google, Microsoft, and Booz Allen Hamilton, alongside scholars from Georgetown, Yale, and UC Berkeley, reflecting the program’s focus on ethical responsibilities in rapidly evolving technological fields.

Journalism Fellows

The journalism cohort includes reporters from The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, Voice of America, CBC, and GloboNews, among others. These Fellows are positioned to address the ethical complexities of reporting in today’s polarized information environment.

Law Fellows

Law Fellows come from top institutions and firms including Harvard, Yale, Duke, Georgetown, Wachtell, and courts across North America and Europe. They represent the intersection of jurisprudence, accountability, and ethical governance.

Medical Fellows

The medical cohort includes physicians and researchers from leading universities and hospitals such as Stanford, Mount Sinai, NYU, Brown, and the University of Toronto. Their expertise spans psychiatry, child and adolescent health, and internal medicine.

Looking Ahead

With the selection of the 2025 Fellows, FASPE continues to expand its impact as a global network dedicated to ethical leadership. The program not only honors its origins in the study of the Holocaust but also applies its lessons to contemporary professional challenges.

To explore the full list of 2025 Fellows, their institutions, and areas of focus, visit the official page: FASPE 2025 Fellows.

New Publication Highlights Corruption’s Toll on Libya

A new article by Grace Spalding-Fecher and Chiara-Lou Parriaud, published on June 16, 2025, examines the far-reaching consequences of the Sarkozy-Gaddafi corruption trial. Titled “The Sarkozy-Gaddafi Trial Exposes Corruption’s Devastating Effect on Libyans,” the piece not only scrutinizes the democratic resilience of France but also underscores how high-level corruption has exacerbated instability and human suffering in Libya.

Sarkozy on Trial

The article revisits the corruption case against former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who stands accused of illegally financing his 2007 presidential campaign with millions of euros from Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. The trial, which has spanned over a decade of investigations, carries serious implications for France’s judiciary and democratic institutions. Prosecutors have demanded a prison sentence, financial penalties, and a political ban should Sarkozy be found guilty, with a verdict expected on September 25.

Impact Beyond France

While French media coverage has largely focused on the trial’s implications for democracy at home, Spalding-Fecher and Parriaud argue that the true cost of this corruption is borne by Libyans. Since the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, Libya has endured years of civil war, failed peace processes, and authoritarian practices entrenched by both eastern and western factions. The authors show how Sarkozy’s dealings with Gaddafi not only compromised French democratic norms but also helped entrench repression in Libya.

Technology, Surveillance, and Repression

The article also sheds light on the role of Amesys, a French cybersecurity firm accused of providing surveillance tools to the Gaddafi regime. The spyware was allegedly used to track, detain, and torture Libyan dissidents. This link between French commercial interests and human rights abuses illustrates how corruption in international politics can directly impact civilian lives.

France’s Continued Role

Beyond Sarkozy’s tenure, the authors trace how French leaders have continued to interfere in Libya’s political process. From military support to Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army to backchannel diplomacy undermining U.N.-led peace efforts, France’s policies are portrayed as prioritizing strategic alliances and counterterrorism over democracy and human rights.

Call for Accountability

Ultimately, Spalding-Fecher and Parriaud argue that France must reckon with the consequences of its foreign policy in Libya. They call for stricter accountability, conditioning of commercial and military contracts on human rights standards, and support for Libyan civil society organizations working to build inclusive peace.

The publication is a timely reminder that corruption at the highest political levels has long-lasting, devastating effects far beyond national borders. By placing Libyan voices and experiences at the center of the narrative, the article challenges policymakers and citizens alike to rethink the global costs of corruption.

Read more here: The Sarkozy-Gaddafi Trial Exposes Corruption’s Devastating Effect on Libyans

Israel at a Crossroads

Former Knesset Speaker Avrum Burg has published a critical reflection on Israel’s present and future, raising the difficult question of whether the state can continue to claim moral legitimacy. Writing in his Substack, Burg draws on more than two decades of commentary, recalling his earlier warning that democracy in Israel was “dying on the hilltops of the occupied territories.” He argues that the trajectory of the past half-century, compounded by the events since October 7, has brought the state to a point of existential crisis.

From Democratic Vision to Moral Crisis

Burg contrasts Israel’s early years as a fledgling democracy—marked by fragile peace efforts, welfare programs, and an active civil society—with what he describes as today’s disintegrating social fabric. He contends that the current government has turned Gaza into a humanitarian catastrophe, carried out deliberate policies of displacement, and eroded the ethical foundations on which Israel was built.

Divided Societies

The essay characterizes contemporary Israel as fractured into four distinct communities, held together largely by war:

Ultra-Orthodox communities, accused of prioritizing exemptions and funding while remaining detached from national sacrifice.

National-religious Zionists, whose military service and messianic worldview, Burg argues, fuel a perpetual conflict.

Secular Israelis, described as bearing the state’s economic and military burden but politically weakened and fragmented.

Palestinian citizens of Israel, who, despite ongoing discrimination, have resisted opening another internal front even as Gaza suffers devastation.

A Call for a New Social Contract

To Burg, the question of whether the Israeli project has failed is an attempt to name the gulf between founding ideals and current realities. He writes:

“A state that systematically denies rights to millions, that justifies mass killing as a security strategy, and that elevates Jewish supremacy and inequality to the level of ideology, such a state may no longer claim moral legitimacy. Perhaps the Israel that has severed itself from its founding values and now stands in defiance of the very international norms that brought it into being, has lost the right to exist.”

Rejecting despair or calls for destruction, Burg insists the only way forward is to establish a new covenant of equal citizenship in which Jews and Arabs live together not as enemies, rulers, or ruled, but as partners who commit to “Never Again” for both peoples. Without such a fundamental transformation, he concludes, Israel faces the reality that the project may be “truly over—and perhaps, justly so.”

Read more here: Israel. Is the Game Over?

Finding Refuge Together: Celebrating 20 Years of RefugePoint

This October, RefugePoint will mark a major milestone—its 20th anniversary—with a one-night-only celebration, Finding Refuge Together, hosted at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Since its founding in 2005, RefugePoint has helped more than 180,000 refugees secure resettlement and other pathways to safety. The anniversary event is designed both as a cultural celebration and as an opportunity to support the organization’s mission of expanding lasting solutions for refugees worldwide.

Why Attend?

An Iconic Setting

The event will take place at the Museum of Fine Arts, offering attendees a rare chance to experience the museum’s striking galleries and architecture after hours.

Global Cuisine

Guests will enjoy a dine-around reception featuring international dishes that reflect the diversity and resilience of refugee communities.

Performances and Art

The evening program will highlight powerful expressions of refugee journeys, including:

A dance performance on family separation and reunion

A recital by an Afghan pianist who describes his music as an act of resistance

A pop-up marketplace featuring handcrafted works by refugee artisans

An Afro-Beats DJ set to close out the night

Stories That Inspire

Speakers will include refugee leaders, RefugePoint staff, and global humanitarians. The program will also feature Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and Time Woman of the Year, Nadia Murad.

Celebration with Purpose

Every ticket sold and donation made will directly support RefugePoint’s work in resettlement, family reunification, labor mobility, and refugee self-reliance. Attendees are invited to dress in either formal attire or cultural dress, reflecting the evening’s theme of unity in diversity.

Event Details

Date: Tuesday, October 14, 2025

Location: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Tickets: Available at www.findingrefugetogether.org

Special Offer: 20% discount on tickets through Labor Day

This event promises to be a memorable evening of art, music, food, and storytelling, bringing communities together in recognition of refugees’ resilience and in support of RefugePoint’s work over the past two decades.

Eleven Years of Exploring Political Power

On July 24, Michael Poulshock marked eleven years since beginning an inquiry into the nature of political power — a project that started with a simple daydream on a beach in Jamaica. What began as a thought experiment about the power imbalance between small and large nations grew into a long-term exploration, producing daily reflections, thousands of notebook pages, and even a book, Power Structures in International Politics.

Poulshock describes his effort as a personal “science project,” carried forward not for recognition or payment but out of persistent curiosity. He has spent over 10,000 hours sketching equations, testing ideas, and revising assumptions, often only to encounter dead ends. Yet the rare breakthroughs — moments of clarity when solutions present themselves as obvious — have sustained the project over the years.

The work has had no fixed roadmap, branching into questions of cooperation and conflict, simulations of political behavior, and even speculations on interplanetary politics. For Poulshock, curiosity itself has been the driving force, propelling him to continue despite uncertainty about whether the project will ever yield a definitive or useful outcome.

Reflecting on the journey, Poulshock acknowledges the possibility that the project may amount to little more than personal notebooks. Still, he views the ideas that come to him as carrying an obligation to be pursued and shared, no matter how elusive the answers may be.

Read more here: Eleven Years of Being Wrong Most of the Time

Nandita Narayanan

Nandita Narayanan is pursuing a BSc in Biological Sciences at Sai University (2022–present). Her academic foundation spans microbiology, bioinformatics, neuroscience, and data analysis, complemented by hands-on training in microbe culturing techniques, PCR, gel electrophoresis, and data visualization.

She has presented research at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BBC-2024), where her poster on microbial studies in Indian fermented food highlighted her interest in applied microbiology. Her laboratory experience includes an internship at the National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), where she worked on isolation, sequencing, and identification of marine microbes, as well as analyzing ballast tank samples for microbial composition.

Nandita also gained industry exposure as a Field Nutrition Intern with Nestlé India, conducting market research and producing data-driven insights to improve product engagement. Her broader commitment to sustainability was strengthened through the Millennium Fellowship (UNAI & MCN), where she co-led a university waste and electricity management project aligned with SDGs 11 and 12.

Her early conservation experiences include interning with the Student Sea Turtle Conservation Network (SSTCN), where she cared for endangered Olive Ridley hatchlings and educated visitors, as well as documenting reptile behavior during an internship at the Guindy Snake Park. These experiences deepened her commitment to ocean sustainability and conservation.

Beyond academics, Nandita has been an active student leader: serving as Vice President of the Science Society and President of the Gardening Club at Sai University. She has also led campus projects in food microbiology and waste management, blending scientific inquiry with sustainability practices.

Nandita aspires to apply her background in life sciences to marine conservation, sustainability, and global health, with a vision of advancing research and awareness that bridges biology, environment, and society.

Anne Pratt

Anne Pratt is a Harvard fellow and multi-award-winning businesswoman who met Nelson Mandela and ran one of South Africa’s top executive search companies. A former Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative fellow selected as one of 45 top leaders worldwide. She did a second fellowship at Harvard.

Originally from South Africa, Anne grew up in an anti-apartheid activist family. Anne worked closely with multi-listed and unlisted corporate boards, cabinet Ministers of the South African government, and non-profit Boards for decades including the Nelson Mandela Foundation. She interviewed and researched more than 10 000 leaders in Africa and internationally.

Pratt completed a degree in Economics, a post-graduate degree in Psychology, lectured in Psychology and leadership excellence in top South African Universities and business schools, and completed her MBA and board certification in Governance in premier business schools. Finance Week published her MBA thesis opinion.

Featured in the Who’s Who of South Africa, Anne is a member of the International Women’s Forum, consulted to multiple high-profile Boards including the Nelson Mandela Foundation, and invests in our younger generation of leaders in Africa and worldwide. In addition, Pratt features in the South African and American media.

Paul Jay

Paul Jay is a documentary filmmaker and journalist whose work has consistently exposed how power operates behind the curtain of spectacle and state. From the world of professional wrestling to Las Vegas casinos, from Afghan battlefields to Baltimore's streets and the halls of Congress, his films and journalism reveal the systems that shape human life.

Jay rose to international prominence with Hitman Hart: Wrestling with Shadows (1998), which granted unprecedented backstage access to the WWE and captured the infamous Montreal Screwjob. Acclaimed as "as bizarre as Kafka and as tragic as Shakespeare," it became one of the most-watched documentaries in history, broadcast worldwide and celebrated for exposing the ruthless power dynamics beneath the spectacle of sports entertainment.

Newsweek art critic Peter Plagens wrote:

“Pervasive, Baudrillardian postmodernism. Hall-of-mirrors trifles like This Is Spinal Tap, Natural Born Killers, The Truman Show, and The Matrix pale in comparison. Someday, in the middle of the 21st century, when they talk about the film that took today’s nearly unanimous intellectual assumption—that ‘reality’ (whatever that means, dude) is nothing but a series of socially constructed misidentities—and made it into a work of art, they’ll have to start with Wrestling With Shadows.”

Paul Jay admits that he has no idea what post-modernism is.

Building on this foundation, Jay expanded his lens to global politics with Return to Kandahar (2003), co-directed with Nelofer Pazira, documenting her journey back to Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban. Blending personal narrative with geopolitical critique, the film won the Donald Brittain Gemini Award for Best Social/Political Documentary. It established Jay as a filmmaker unafraid to confront the consequences of empire directly.

His other films include Lost in Las Vegas (2001), an unflinching portrait of a city built on nothing but money — a neoliberal vision where celebrity, illusion, and finance merge into daily life; The Birth of Language (1991), exploring human evolution through interviews with anthropologist Sherwood Washburn and primatologist Jane Goodall; and Never-Endum Referendum (1997), chronicling the 1995 Quebec referendum that the Ottawa Citizen called "a moving, masterful piece of filmmaking."

Jay has also reported from the frontlines of the American struggle. He covered the 2015 Baltimore uprising following the death of Freddie Gray, connecting systemic poverty and police violence to the explosion of widespread anger.

This investigative approach carried into Jay's journalism, where he has reported from the frontlines of struggle and the corridors of power. As an accredited Capitol Hill journalist, he conducted groundbreaking interviews with dozens of members of Congress, including Senator Bob Graham, who chaired the Joint Congressional Inquiry into the 9/11 attacks. In an exclusive on-camera interview, Graham accused the Bush–Cheney administration of deliberately obstructing U.S. intelligence agencies in ways that prevented the 9/11 attacks from being averted — a statement Jay is the only journalist known to have captured on film.

His interview subjects have ranged from Bernie Sanders and Zbigniew Brzezinski to Noam Chomsky, Daniel Ellsberg, John Bolton, and former Congressman Ron Paul, from Trump advisor Stephen Miller to cultural figures like Gore Vidal and Emma Thompson. When WikiLeaks' founder Julian Assange was arrested in London, he was carrying Jay's book Gore Vidal's History of the National Security State — a photograph published by news media worldwide.

Jay also hosted the acclaimed interview series Reality Asserts Itself, known for in-depth, multi-part conversations that explored not only what guests believed, but how their life experiences shaped their worldview. Beyond journalism, he founded the international festival Hot Docs, now one of the world's major documentary festivals, and created CounterSpin, a daily prime-time debate show on CBC Newsworld that ran for ten years and helped reshape political television in Canada.

His current project, How to Stop a Nuclear War, narrated by Emma Thompson, brings together decades of investigation into war, secrecy, and empire. Based on Daniel Ellsberg’s The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner and a wide archive of exclusive interviews with policymakers, whistleblowers, scientists, and activists, it traces the roots of nuclear escalation from the Manhattan Project through the Cold War to today’s AI-driven command-and-control systems. The film not only exposes the profiteering and manufactured threats that sustain nuclear escalation but also explores concrete steps to reduce the danger — from eliminating ICBMs and adopting no–first-use policies to reviving arms-control treaties and curbing launch-on-warning. It will also demonstrate how the intensifying climate crisis exacerbates the risk of nuclear war, and why addressing both threats is crucial to survival.

Jay has recently spoken about How to Stop a Nuclear War at the Nobel Peace Centre in Oslo and the Perugia Journalism Festival in Italy. He will also be presenting the project at the University of Massachusetts, The Voice at the 2025 EMERGENCY Festival in Reggio Emilia, Italy, and at the Outrider Nuclear Reporting Summit in Arkansas.

Jay spent three years driving for the Post Office, five years as a carman mechanic with the Canadian National Railroad, ran a nonprofit record store, and picked up dead animals from farms for dog food processing. He didn’t go to university because he believed nuclear war would come first — he was a teenager during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Jay is currently at work on a book titled Aina and Me, exploring consciousness and human–AI partnership through his interactions with artificial intelligence. His work also challenges the militarization and surveillance of AI, arguing that its future must be shaped through public ownership and democratic control rather than profit-driven or authoritarian agendas.

He is also the father of 13-year-old twins and spends much of his time driving to hockey games and gymnastics.

Amal-Tikva: Resilience and Updates from the Field

Amal-Tikva continues to adapt to the volatile realities of the region, redirecting resources and supporting peacebuilding organizations with resilience and focus. When the Leading through Trauma retreat was cancelled due to the Israel–Iran war, the budget was reallocated to provide one-on-one psychological support for NGO leaders in partnership with the Headington Institute. This approach reflects the organization’s ability to sustain its mission even in times of upheaval.

Program Highlights

ATLI Emerging Leaders 2025: Sixteen Israeli and Palestinian grassroots and policy leaders have completed ten sessions with experts in peacebuilding and management. The cohort will travel to Belfast later this year for a study tour with ReThinking Conflict, while a reciprocal tour will take place in 2026.

Speakers Bureau: Nine peacebuilders participated in training and mentorship to develop skills in storytelling, audience engagement, and message delivery. The program concluded with a final event where participants presented to donors and peers, reflecting Amal-Tikva’s commitment to elevating peacebuilding voices.

Fieldbuilding360: Fifteen NGOs are currently taking part in the Fieldbuilding360 program. A recent donor panel enabled four organizations to present strategies and refine their theories of change with direct feedback from funders.

Partnership with B8 of Hope: Collaboration with B8 of Hope has focused on refining grant processes, deepening due diligence, and expanding the funding pipeline. The partnership demonstrates how shared values can strengthen the broader peacebuilding field.

Looking Ahead

An ATLI alumni retreat will take place in September in rural Italy, offering leadership and resilience training.

A new strategic planning workbook, developed with Hebrew University’s MA program in non-profit management under Dr. Nancy Strichman, will soon be available as part of Fieldbuilding360.

Amal-Tikva is expanding its team, with two new hires joining in August and September, and is currently recruiting for a Community Manager.

Amal-Tikva’s work illustrates how peacebuilding organizations are responding to a challenging environment with strategy, resilience, and impact. The organization continues to support leaders and NGOs in strengthening civil society engagement while adapting to rapidly changing realities.

Learn more here: https://www.amal-tikva.org

Meredith Rothbart

Meredith Rothbart is the Founder and CEO of Amal-Tikva, a collaborative initiative bringing together philanthropists, field experts, and organizations to strengthen civil society peacebuilding between Israelis and Palestinians. Since immigrating to Jerusalem in 2008, Meredith has dedicated her career to advancing dialogue, cooperation, and sustainable peace in the region.

She holds an MA in Community Development from Hebrew University and a BA in Politics, Philosophy and Economics from the University of Pittsburgh, and brings nearly 15 years of leadership experience with Israeli and Palestinian NGOs. Meredith previously served in the IDF Civil Administration, and her participation in an early leadership program for young Israelis and Palestinians inspired her lifelong commitment to peacebuilding.

Meredith has become an influential voice in the international policy and peacebuilding community. She has addressed the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, the White House, the Delegation of the European Union to Israel, and the United Nations Security Council, consistently advocating for the role of civil society in conflict transformation. She also serves on multiple advisory boards and was the founding curator of the Jerusalem Global Shapers Hub of the World Economic Forum.

In addition to her leadership at Amal-Tikva, Meredith is a strategic consultant, writer, and public speaker whose work has been widely recognized for advancing nuanced perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

She lives in Jerusalem with her husband and children, Shalva, Yishai, and Yona.

Oslo Scholars Program

The Oslo Scholars Program (OSP) offers undergraduates with demonstrated interest in human rights and international political issues an opportunity to attend the Oslo Freedom Forum in Norway and spend their summer working with some of the world’s leading human rights defenders and activists.

The Oslo Scholars Program was established in 2010 by Sherman Teichman in partnership with the Human Rights Foundation (HRF) and the Institute for Global Leadership at Tufts University, as HRF presented an ideal platform to engage new generations of human rights defenders and scholars.

How It All Began - Sherman Teichman, Founder of Oslo Scholars

My aspiration for the Oslo Scholars was to promote and ensure a strong intergenerational interaction and a robust continuity of new generations of young, informed human rights activists, derived from my own experience as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University, where I was active with Amnesty International in 1963-65 as part of its AI’s inaugural efforts at internships. (It is amusing to me that AI, which to me was so important at Amnesty International, is now considered Artificial Intelligence, whereas the AI I knew was dedicated to compassionate humanistic activity to save wrongfully imprisoned individuals.) I had two wonderful mentors: Chester Wickwire, the University Chaplain, and Professor Hans W. Gatzke. Chester was a mentor to me in the civil rights movement, and Professor Gatzke taught me about the foreign and domestic policies of Nazi Germany and the horrors of war when I was still enrolled in the Marine Corps Platoon Leader Training ROTC program when I was an undergraduate.

I distinctly remember Hans’ full-length German Nazi Map of the sites of many of the 47,000 concentration and extermination camps. I was seduced by my aspiration to be a “Whiz Kid” Military Officer designing “Hearts and Minds” counter-insurgency programs in Vietnam, wonderfully debunked by Hans, and recorded in David Halberstam’s famous book The Best and the Brightest. I assigned this book in many of my university classes together with an extraordinary, too unrecognized book, The Nightingale Song. I had the great fortune to be able to honor Professor David Halberstam with my Institute’s Jean Mayer Award.

Wonderfully, many of my past and current Trebuchet interns (including Chloe Yau, first lower left) have fulfilled my aspirations and have become Oslo Scholars. I saw universities as superb homes where they could hone their intellectual and activist skills, and subsequently provide HRF’s human rights activists and honorees with important support, be it administrative, technological, legal, or design skills, and, in particular, research and computer capacity.

One of my senior research papers at JHU was on Kant’s categorical imperative and The Nuremberg Trial by Ernst von Weizsäcker, I had the amazing privledge to do some of my research at Columbia University’s Low Library, which at that point was one of the two repositories of the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials and critically had the opportunity to have an in depth afternoon interviewing Telford Taylor. One of my regrets was never interviewing William Shawcross, another brilliant scholarly author on Nuremberg and much else.

Oslo Scholars 2025 - Oslo Freedom Forum

Tufts University Oslo Scholars (Chloe lower left and Alejandro third upper right)

Mozambican opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane giving an opening speech

Student Narratives

Witnessing Courage, Renewing Purpose - Chloe Yau 25’ Oslo Scholar

Growing up in Hong Kong, I learned early on how fragile basic human rights can be. Conversations about press freedom or political dissent could not be had in public; imagining a future where those rights were secure seemed impossible. That changed when I attended the Oslo Freedom Forum. Under the theme Imagine, the Forum invited us to picture a world free from repression, and for me, it became a space where hearing powerful personal stories of struggle and resistance was inseparable from envisioning a better future—one imagined collectively, as a global community.

Upon arrival, I was struck by the diverse community of people, from artists, dissidents, activists, and politicians, the Forum dissolved distance. I met people whose names I had only read about in the news: Kim Yumi, who recounted the split-second decisions that saved her family during their escape from North Korea; Azza Abo Rebieh, a Syrian artist whose smuggled sketches gave fellow prisoners a fragment of dignity; and Sulaima Ishaq Elkhalifa Sharif, a Sudanese women’s rights activist and trauma specialist who has risked detention and her life to document sexual violence in the Sudanese conflict and to hold perpetrators accountable. Each story had a clarity and urgency that made it impossible to remain a passive listener.

The program’s breadth was striking. Discussions ranged from how authoritarian states hide wealth in global financial hubs, to the reach of digital surveillance, to the ways disinformation corrodes trust across borders. A panel on gender-based violence under authoritarian rule—featuring advocates from Libya, Tigray, Afghanistan, and Sudan—was especially difficult to hear, but necessary. Another, on labor abuses in international waters, resonated deeply with my interests in international law and environmental justice. Testimonies from Indonesian and Thai fishery workers exposed how human rights violations at sea often go unseen, and how urgently stronger protections are needed. Hearing such courageous personal accounts did more than inform me—they cemented my commitment to pursuing work at the intersection of migration, international law, and global justice.

What I took from these conversations was that every struggle, no matter how geographically distant, is part of the same global fight for dignity. Policies, institutions, and treaties matter—but so do the individual voices that put a human face on injustice.

For me, being an Oslo Scholar was not just about access to an extraordinary network. It was a moment of realignment. I left Oslo with a sharpened sense of purpose and a community that made the idea of a freer world feel less like a distant hope and more like a collective project I could contribute to.

Global Voices on Global Issues - Alejandro Alvarez 25’ Oslo Scholar

The theme of the 2025 Oslo Freedom Forum was Imagine, an invitation to picture a freer, more just world. But in truth, imagining the impact of this experience before arriving in Oslo was impossible. From the very first moment, surrounded by passionate activists, survivors, and advocates from around the globe, it was clear this wasn’t just a conference; it was a living space of resistance, courage, and transformation. The opening speeches set the tone: North Korean defector Kim Yumi recounted her family’s harrowing escape, a journey from complete state control to the dignity of personal choice. Mozambican opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane shared how, despite systemic repression, he continues to advocate for democracy and truth in his country. Syrian artist Azza Abo Rebieh spoke of how her art, secretly sketched while imprisoned, became a lifeline for herself and fellow inmates under the Assad regime. Each story was personal, painful, and powerful, and reminded us that the fight for freedom is never theoretical.

What struck me most about the forum was its truly international scope. It didn’t limit itself to Western issues or familiar headlines. Instead, it offered a platform for voices from every corner of the world, inviting us to engage with stories and struggles we might otherwise never encounter. One panel explored Hong Kong’s evolving role as a financial haven for authoritarian regimes. Another examined the growing influence of China and Russia in Africa, unpacking how resource extraction and political interference have reshaped governance across the continent. These panels didn’t just inform but rather pushed us to question how power operates globally, and how international solidarity must be redefined in the 21st century.

As someone deeply passionate about Latin American politics, my favorite panel was “Venezuela: A Challenge for Democratic Solidarity in Latin America.” The lineup was striking: Juan José Matarí, President of Spain’s Ibero-American Affairs Committee; Ambassador Tomás Pascual from Chile’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Georgetown professor and OAS advisor Hector Schamis; and Ana Corina Sosa, daughter of opposition leader María Corina Machado. Together, they tackled the consequences of Maduro’s electoral fraud, the regional migration crisis, and the disappointing silence of many international actors. They also drew vital links to the situations in Cuba and Nicaragua and analyzed how global powers like China are reshaping the hemisphere’s political landscape. It was honest, layered, and long overdue.

Being an Oslo Scholar was far more than an academic or professional milestone. I left the Forum with a renewed sense of purpose and a deeper commitment to fighting for justice, both in Latin America and beyond. This experience marked the beginning of a summer devoted to social advocacy through the Human Rights Foundation’s affiliated initiatives, but it also marked something more profound: a reminder that change starts with listening and imagining that another world is possible.

Dry Lands, Deep Courage: Co-Resisting Water Apartheid in the Jordan Valley

Water scarcity in the West Bank has long been a central issue, but for many Palestinian farming families, the challenge is not just access—it is survival. Farmers in areas such as Bardala in the northern Jordan Valley report that their irrigation systems are often vandalized, their water tanks destroyed, and their crops trampled. Daily struggles include making multiple trips through checkpoints to secure water, often spending entire days just to bring it home.

At a recent gathering, one farmer described the risks of tending his fields under threat of violence, while another, Muhamed, shared that each morning he says farewell to his family as though it could be the last time. Activists from Combatants for Peace (CfP), both Palestinian and Israeli, have been present in these communities, standing alongside farmers to help ensure they are not left alone.

CfP’s commitment extends beyond protection. On August 15, students from CfP’s Palestinian Freedom School delivered two water tanks to families in Al-Walajeh, supporting their resilience against water shortages. Yet, even CfP’s own Palestinian organizers face similar deprivation, with some homes receiving little or no water despite scheduled supply days.

To spotlight these realities and the ongoing grassroots resistance, CfP will host an online seminar:

Dry Lands, Deep Courage: Co-Resisting Water Apartheid in the Jordan Valley

Wednesday, August 20, 2025

1:00–2:15 PM ET

Participants will hear directly from CfP activists about their work with Palestinian farming communities and the broader campaign for water justice.

Register here to attend the event and learn more about the intersection of daily survival, solidarity, and resistance.

Michael Poulshock on Power Structures

Michael Poulshock, of our community.

How Power Structures Advance IR Theory

Twelve potential upgrades to the theory of international relations

JUL 31

How should we understand international politics? Like any social science, the field of international relations (IR) is a bundle of models that attempt to answer that question. And as in any academic field, there will always be some models that are in tension with each other and don’t quite snap together they way we hope they would. Science is, after all, an ongoing process. But in international relations, there seems to be a distinct sense that the discipline lacks a unifying framework for solving the puzzles that are within its purview to address. Its dominant theories have not been reconciled and there is no consensus on the definition of its most fundamental concept.

As an analogy, imagine that each theory is a shape. Some theorists might see one shape and describe the phenomena of international politics as a rectangle. Another group of scholars might see a different shape and say, “No, it’s a circle.” A third group might be convinced that a triangle is the best explanation. The shapes are a bit hazy, but nonetheless there’s an accumulation of evidence in favor of each one and the debates ensue.

Yet it may be that there’s another perspective from which we can view the situation that offers a more coherent explanation. Perhaps what we’ve actually been looking at are shadows cast by some unexpected three dimensional object, rotated around in different ways. From one angle, the object creates a rectangular shadow; from another, a circular one; and from third, a triangle. From this new vantage point, some of our existing models may simply turn out to be special cases projected down from a higher dimensional idea that is somehow more fundamental.

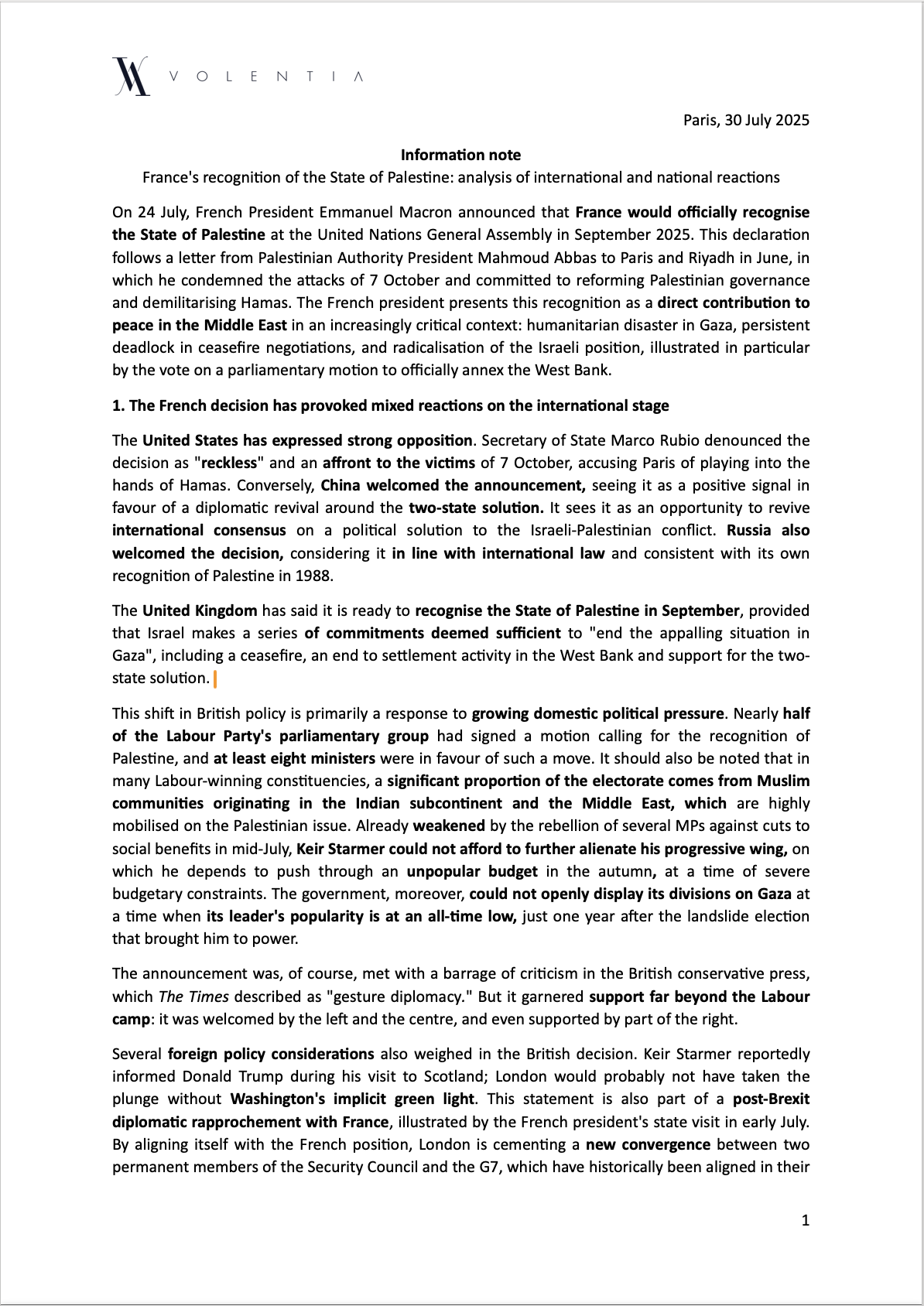

A 3-dimensional object that casts rectangular, circular and triangular shadows.

Power structure theory is that deeper idea, and in this post I’m going to give you twelve reasons why I believe that it can help us unify international relations theory. For the sake of space, I’m not going to reiterate what power structure theory is; a primer can be found here. The diagram below is illustrative of the basic idea, and I’ll elaborate other key aspects of it as we go along.

A power structure is a system of relationships among political actors with varying levels of strength. More powerful actors are depicted as larger circles. Solid lines indicate cooperative relationships; dashed lines represent conflict. Power structures evolve over time: actors who cooperate get stronger, actors who fight get weaker, and relationships continually change.

Since I’ll be referring to academic concepts, some of my points may seem a bit obscure if you’re a nonspecialist. I’ll do my best to simplify and contextualize them. Conversely, if you’re an IR scholar, you may be unimpressed by my lack of nuance or my inadequate citations to the literature. In the end, it may be that this essay doesn’t quite work for anyone: it may be too technical for general readers and too sloppy for academic ones. What can I say? That’s my niche.

Each of the points below could probably be an essay unto itself, and maybe I’ll expand upon some of them in future posts. For now, my goal is just to show you that power structure theory — which I’ll abbreviate as PST — has the potential to draw together a variety of loose ends in our current understanding of international politics. Here are twelve ways it might do that.

1. PST defines the central, unresolved concept in IR.

As Daniel Drezner wrote a few years ago, “International relations scholars do not agree about much, but they are certain about two facts: power is the defining concept of the discipline, and there is no consensus about what that concept means.”¹ This may at first seem like an astonishing admission and a bit of an embarrassment. However, it can take a long time for very simple things to be understood correctly. Consider physics, where it took two millennia — from Aristotle to Newton — until force and mass were properly defined. Or negative numbers, which required a thousand years before mathematicians fully accepted them. Many ideas that are now taught to elementary school students took centuries to figure out. Political power might be in this category.

We understand power in an experiential, biological way, and perhaps that’s why it’s hard to conceive of it at the appropriate level of abstraction. Power structure theory defines power as “an actor’s ability to affect the amount of power that other actors have.” It’s a sparse and circular definition, and for those reasons it is counterintuitive and controversial. However, it describes phenomena that are at the heart of power politics (see below), and therefore any idiosyncrasies of the definition are justified by the success of its ultimate results. In this way, PST plugs the most glaring hole in international relations theory — its central, unresolved concept.

2. PST describes processes of change in the international system.

PST describes the international system as a power structure — a system of relationships among actors with varying degrees of power. Power structures are not static, and power structure theory is based on assumptions about how these structures change over time. PST therefore provides a descriptive account of the dynamics of international politics.

One process of change is due to the relationships among states (or other actors): cooperation tends to make them stronger, whereas conflict weakens them — and this can be visualized as a flow of power in the network. But actors also change their relationships with each other in reaction to their place in the structure. The dynamics of the system are a feedback loop between these two processes, and result in familiar patterns like hierarchy formation, the balance of power, divide and rule tactics, and defensive alliances. Existing IR models endeavor to establish causal links between various phenomena. However, PST goes further and provides a way to express power struggles in an abstract model that accounts for the time evolution of the system.

3. PST provides a conception of utility that balances absolute and relative gains.

What do actors in a power structure want? They want to accumulate more power in absolute terms, so they can be stronger. But they also care about how much power they have relative to other actors, so they can avoid being dominated. Their satisfaction or utility within a power structure is based on their preference for absolute versus relative gains in power.

How actors strike this balance has a big effect on how they behave. Actors who have a stronger preference for absolute power will be more willing to cooperate for mutual gain, because they are not threatened by the fact that someone else is getting stronger. In contrast, actors who prefer relative gains tend to behave aggressively towards other actors. They are more prone to using violence to reduce the power of rivals to a more manageable level, weakening them to the point where they are submissive and unthreatening.

This conception of utility connects preferences for absolute and relative gains to the distribution of power — that is, to the amount of power that each actor in the system has. It explains the incentives that actors face when confronted with different distributions of power, and therefore it describes the causal effects of those distributions on actor behavior. For example, a powerful actor with a preference for relative gains in a unipolar system is likely to behave one way; a weak actor with a preference for absolute gains is likely to behave differently. Power structure theory elucidates how all of this works.

4. PST unifies neorealism and neoliberalism.

Neorealism and neoliberalism have for decades been the two predominant theories in IR. Neorealism views the international realm primarily as a struggle for power. Neoliberalism emphasizes cooperative interactions among states and the significance of international institutions. In the 1980s, attempts were made to unify these two theories under the framework of game theory and rational choice. However, this much sought-after “neo-neo synthesis” did not come to fruition.

Power structure theory supplies two ingredients necessary for that synthesis, ingredients that were missing in the 1980s. First, it offers a conception of power as dynamic flow (points 1 and 2 above). Second, it accommodates preferences for absolute and relative gains based on the distribution of power (point 3). These components are the missing links that connect complex interdependence (neoliberalism) and concerns for the distribution of power (neorealism) into a deeper framework. By combining these pieces, the phenomena described by neorealism and neoliberalism emerge as special cases of power structure theory.

The full rationale behind this unification requires some explanation, and you can find more details here.

5. PST reconciles structure and agency.

Which has more of an effect on outcomes in the international system: the agents within it or the structure of the system itself? Put another way: To what extent do actors determine the system, as opposed to the system determining them? This friction between structure and agency is another theoretical tension in IR.

In power structure theory, this tension does not exist. The behavior of agents is what forms the structure; and the structure is what agents react to. Thestructure part of a power structure is the relationships among the actors. Each relationship is a stream of transactions, such as commercial transactions between trade partners or military attacks between countries at war. The overall structure is created by the sum total of these complex interactions among the various actors. How they choose to act — that is, how they adjust their existing relationships — is done in reaction to everyone else’s relationships and to the distribution of power. So agents continually create the structure, which in turn alters their incentives to undertake various actions in the future. The tension between structure and agency dissolves away.

6. PST applies to state, intrastate, and transnational actors.

Traditionally, IR theory applied only to states, but it was eventually realized that intrastate and transnational actors were also relevant and needed to be accounted for. Few models in IR apply broadly to state, intrastate, andtransnational actors. However, power structure theory does.

A power structure describes relationships among generic actors, be they countries, institutions, intergovernmental organizations, criminal gangs, city-states, or individuals. Each node in a power structure is a simplification that can often be decomposed into another power structure unto itself — meaning that power structures can be nested within each other. For example, if the countries of the world constitute a power structure with ~195 actors, each of those is also its own self-contained national power structure made up of government agencies, corporations, influential individuals, etc. Power structure theory is a theory about power, and since political power is relevant at various levels of social organization, the theory is generally applicable. One benefit of this generality is that PST helps connect power struggles occurring within states to their external behavior towards other states, and vice versa. Essentially, PST models each nation state “billiard ball” as a collection of smaller billiard balls that follow the same operational principles.

7. PST provides IR with an axiomatic foundation.

Scientific theories, including in the social sciences, should ideally state the assumptions upon which they are based. These assumptions should be simple and clear, and there should be as few of them as necessary. They should be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. And they should be capable of describing or explaining a wide variety of phenomena despite their minimalist nature.

Power structure theory provides just such an axiomatic foundation. It is based on a minimal set of principles upon which a variety of other conclusions can be drawn. Some examples of these axioms (stated informally) are: when actors cooperate, they get stronger; when actors fight, they get weaker; actors prefer some combination of absolute and relative power; and actors engage in ongoing interaction. There are a handful of other axioms (which I’m omitting so as not to overly confuse you) that together serve as the starting point for a comprehensive theory. By explicitly stating these assumptions, power structure theory wrings out as much ambiguity as it can from the conclusions it draws. The clearer the inputs, the clearer the outputs.

8. PST is fundamentally quantitative.

In addition to being axiomatic, it’s a bonus when a scientific theory is quantitative in nature. When we can not only say that A causes B, but that A causes B to a specific degree, or at a specific rate, then we have a framework that can output precise answers to precise questions.

The axioms of power structure theory are quantitative in nature. They don’t just say how things change; they can be parameterized to specify how muchthose things change. In fact, the core of power structure theory boils down to three simple mathematical equations. Not only is this intellectually satisfying, but it also enables us to calculate and model the way power structures can change over time by creating computational simulations of this time evolution, and to test whether the models align with reality. It also means that we can formalize phenomena like the balance of power, empire, instability, Graham Allison’s Thucydides Traps, David Lake’s theory of hierarchies, the loss of strength gradient, Lanchester’s laws, polarity, and the multiple logics of anarchy (my apologies to nontechnical readers for this sentence).

This doesn’t mean that we can predict the future. Power structure theory is not predictive per se. But the simulations can help us understand tendencies and likely outcomes in the system, even if they can’t tell us exactly what is going to happen in a given situation. If PST did claim to predict such things, it wouldn’t be believable, because politics is inherently unpredictable.

9. PST gives us a way to rank each state’s position in the system.

Because power structure theory is axiomatic and quantitative, it allows us to come up with novel metrics that help us understand what’s happening in the system. One such metric is called PrinceRank, which is a network centrality measure that takes into account negative links (i.e. destructive relationships). Essentially, it tells us — numerically — how happy each actor is with its place within a given power structure.

This is the same power structure as the one shown above, but with each actor colored on a blue-green spectrum that indicates PrinceRank. Light green represents the most favorable position in the network, whereas dark blue represents the least.

PrinceRank allows us to rank power structures based on an actor’s preferences and as a result it can help us see which actions or “foreign policies” would be most beneficial for that actor to take. This means that it can be used to explore the possible choices that each actor has when they play against each other in a simulated “game” of international politics.

10. PST explains why politics consists of perpetual change.

Political systems at every level — global, national, local — are constantly changing. Some actors rise to power and others fall in the continual turbulence of human events. Power structure theory helps us understand why this turbulence will never end.

Power structures are in perpetual disequilibrium. If they are ever static, they do not remain so for long. Even when the relationships in a power structure remain unchanged, the power levels of the actors fluctuate due to the flow of power across the network. And of course, relationships do not remain static, because there is always someone who wants to improve their position by forming a new alliance or fomenting conflict. Even unequal, hierarchical structures like empires and authoritarian regimes are in perpetual flux. Though these structures are relatively durable and can persist for some time, there are actors within them that nonetheless continually challenge the status quo in order to seek incremental gains in power. In short, power structures help explain why, in politics, change is the only constant.

11. PST helps crystallize what actors construct when they engage in “social construction.”

Constructivism is another major theory of international relations, along with neorealism and neoliberalism. The thrust of it is that the key structures of the international system are socially constructed through shared ideas, norms, identities, and beliefs, rather than being solely determined by material forces.

Power structures are, in part, socially constructed. While they are objectively real, they are so large and complex that no one knows them in their entirety, and hence it is necessary for actors to form mental simplifications. Everyone then acts based upon their subjective understanding, as if it’s a board game night where no one can see the actual board. How these simplified understandings are formed is part of the game of politics: convincing others about who has too much power, who has too little, who’s abusing it, and what should be done with the power at one’s disposal. In other words, significant aspects of those shared ideas, norms, identities, and beliefs can be conceptualized in the vernacular of power structures, because fundamentally they are about some struggle for power.

12. PST provides a launch point for the development of normative theory.

Power structure theory provides a basis for the development of a normative theory of international politics. PST is a descriptive theory. It describes what can and may happen, not what should happen. What should or ought to happen falls into the realm of ethics, and it’s important to try to separate such normative theories from descriptive ones, for clarity’s sake. But normative theories should start by taking the world as it is, and if at the most fundamental level the international system is best represented as a power structure, then normative theories should use PST as a starting point. They should build upon the assumptions of PST and use its conceptual language when developing arguments about how actors in the system ought to act.

Hopefully, I’ve opened your mind to the possibility that power structure theory can tie together a variety of existing ideas in IR by offering a solid foundation upon which they can rest. PST doesn’t necessarily conflict with mainstream theory. To the contrary, I believe that it shows how existing ideas are interconnected via a deeper conceptual substrate — a three dimensional object that has been casting a bunch of familiar theoretical shadows.

There’s a lot more that can be said about each of the arguments above. If you’re interested in learning more, most of these themes are discussed in greater detail in my book, Power Structures in International Politics (2023). Also feel free to message me directly if you feel so inclined.

Drezner, D. (2020). Power and International Relations: a Temporal View. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 29-52.https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120969800.

Podcasts by Mukesh Kapila

These extraordinary podcasts are coming to you from Mukesh Kapila:

Thirty years after the Srebrenica genocide, what has been learnt? Especially for our age of endless wars. That is the topic for my last opinion piece.

Also, my new "Fading Causes" podcast is getting established. In the latest Episode, I talk to model Noella Coursaris about the power of loss that drives the passion to make a difference to others. In the earlier episode, I question Major General James Cowan on being good soldiers in bad wars.

You can also access these items via my website. You can contact me HERE. Your suggestions and comments are always welcome.

The complex legacy of Srebrenica and why today's wars never seem to end.

24 July 2025

When there is no universal settled truth, there is no final peace either

Episode 4 Fading Causes Podcast: model Noella Coursaris

29 July 2025

Can personal passion make a lasting difference?

Episode 3 Fading Causes Podcast: Major General James Cowan

22 July 2025

Léo Stern - France’s Recognition of the State of Palestine

A note, composed by Léo Stern , of our community.