Michael Poulshock on Power Structures

Michael Poulshock, of our community.

How Power Structures Advance IR Theory

Twelve potential upgrades to the theory of international relations

JUL 31

How should we understand international politics? Like any social science, the field of international relations (IR) is a bundle of models that attempt to answer that question. And as in any academic field, there will always be some models that are in tension with each other and don’t quite snap together they way we hope they would. Science is, after all, an ongoing process. But in international relations, there seems to be a distinct sense that the discipline lacks a unifying framework for solving the puzzles that are within its purview to address. Its dominant theories have not been reconciled and there is no consensus on the definition of its most fundamental concept.

As an analogy, imagine that each theory is a shape. Some theorists might see one shape and describe the phenomena of international politics as a rectangle. Another group of scholars might see a different shape and say, “No, it’s a circle.” A third group might be convinced that a triangle is the best explanation. The shapes are a bit hazy, but nonetheless there’s an accumulation of evidence in favor of each one and the debates ensue.

Yet it may be that there’s another perspective from which we can view the situation that offers a more coherent explanation. Perhaps what we’ve actually been looking at are shadows cast by some unexpected three dimensional object, rotated around in different ways. From one angle, the object creates a rectangular shadow; from another, a circular one; and from third, a triangle. From this new vantage point, some of our existing models may simply turn out to be special cases projected down from a higher dimensional idea that is somehow more fundamental.

A 3-dimensional object that casts rectangular, circular and triangular shadows.

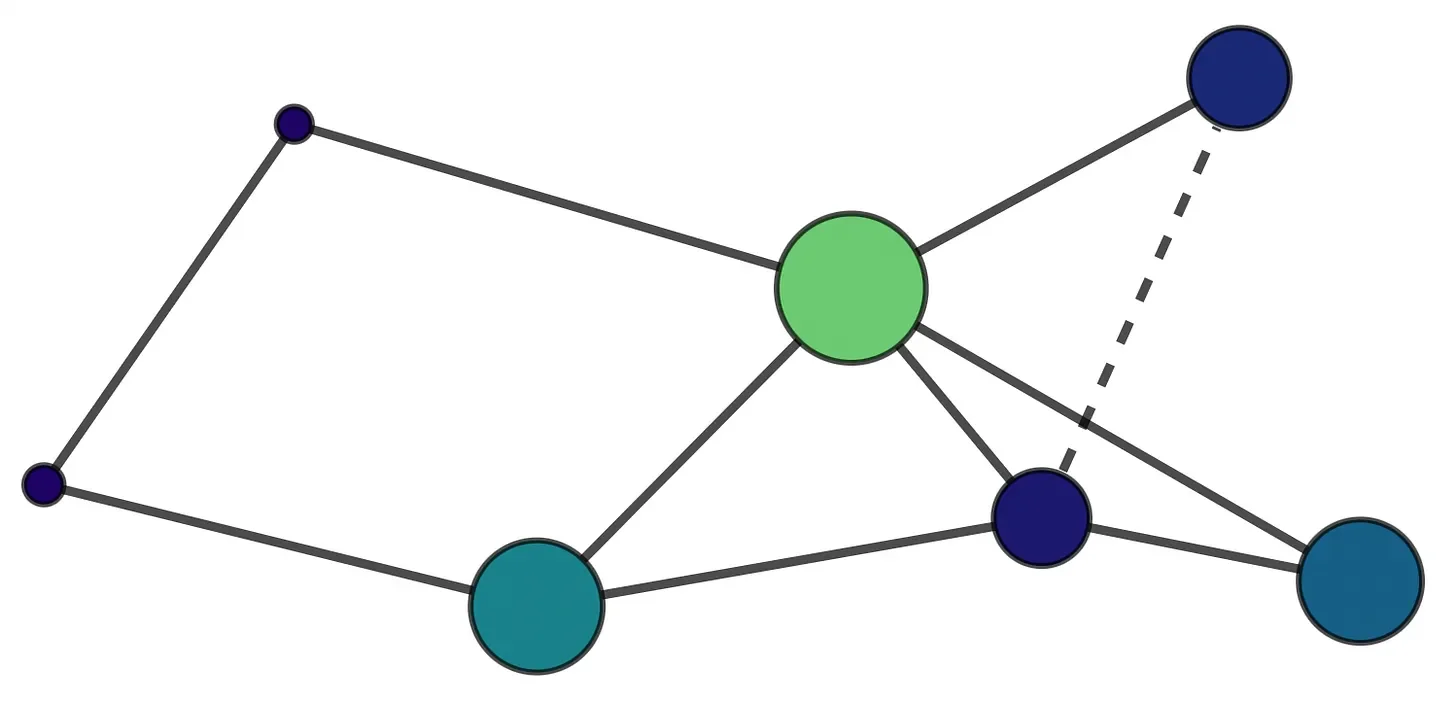

Power structure theory is that deeper idea, and in this post I’m going to give you twelve reasons why I believe that it can help us unify international relations theory. For the sake of space, I’m not going to reiterate what power structure theory is; a primer can be found here. The diagram below is illustrative of the basic idea, and I’ll elaborate other key aspects of it as we go along.

A power structure is a system of relationships among political actors with varying levels of strength. More powerful actors are depicted as larger circles. Solid lines indicate cooperative relationships; dashed lines represent conflict. Power structures evolve over time: actors who cooperate get stronger, actors who fight get weaker, and relationships continually change.

Since I’ll be referring to academic concepts, some of my points may seem a bit obscure if you’re a nonspecialist. I’ll do my best to simplify and contextualize them. Conversely, if you’re an IR scholar, you may be unimpressed by my lack of nuance or my inadequate citations to the literature. In the end, it may be that this essay doesn’t quite work for anyone: it may be too technical for general readers and too sloppy for academic ones. What can I say? That’s my niche.

Each of the points below could probably be an essay unto itself, and maybe I’ll expand upon some of them in future posts. For now, my goal is just to show you that power structure theory — which I’ll abbreviate as PST — has the potential to draw together a variety of loose ends in our current understanding of international politics. Here are twelve ways it might do that.

1. PST defines the central, unresolved concept in IR.

As Daniel Drezner wrote a few years ago, “International relations scholars do not agree about much, but they are certain about two facts: power is the defining concept of the discipline, and there is no consensus about what that concept means.”¹ This may at first seem like an astonishing admission and a bit of an embarrassment. However, it can take a long time for very simple things to be understood correctly. Consider physics, where it took two millennia — from Aristotle to Newton — until force and mass were properly defined. Or negative numbers, which required a thousand years before mathematicians fully accepted them. Many ideas that are now taught to elementary school students took centuries to figure out. Political power might be in this category.

We understand power in an experiential, biological way, and perhaps that’s why it’s hard to conceive of it at the appropriate level of abstraction. Power structure theory defines power as “an actor’s ability to affect the amount of power that other actors have.” It’s a sparse and circular definition, and for those reasons it is counterintuitive and controversial. However, it describes phenomena that are at the heart of power politics (see below), and therefore any idiosyncrasies of the definition are justified by the success of its ultimate results. In this way, PST plugs the most glaring hole in international relations theory — its central, unresolved concept.

2. PST describes processes of change in the international system.

PST describes the international system as a power structure — a system of relationships among actors with varying degrees of power. Power structures are not static, and power structure theory is based on assumptions about how these structures change over time. PST therefore provides a descriptive account of the dynamics of international politics.

One process of change is due to the relationships among states (or other actors): cooperation tends to make them stronger, whereas conflict weakens them — and this can be visualized as a flow of power in the network. But actors also change their relationships with each other in reaction to their place in the structure. The dynamics of the system are a feedback loop between these two processes, and result in familiar patterns like hierarchy formation, the balance of power, divide and rule tactics, and defensive alliances. Existing IR models endeavor to establish causal links between various phenomena. However, PST goes further and provides a way to express power struggles in an abstract model that accounts for the time evolution of the system.

3. PST provides a conception of utility that balances absolute and relative gains.

What do actors in a power structure want? They want to accumulate more power in absolute terms, so they can be stronger. But they also care about how much power they have relative to other actors, so they can avoid being dominated. Their satisfaction or utility within a power structure is based on their preference for absolute versus relative gains in power.

How actors strike this balance has a big effect on how they behave. Actors who have a stronger preference for absolute power will be more willing to cooperate for mutual gain, because they are not threatened by the fact that someone else is getting stronger. In contrast, actors who prefer relative gains tend to behave aggressively towards other actors. They are more prone to using violence to reduce the power of rivals to a more manageable level, weakening them to the point where they are submissive and unthreatening.

This conception of utility connects preferences for absolute and relative gains to the distribution of power — that is, to the amount of power that each actor in the system has. It explains the incentives that actors face when confronted with different distributions of power, and therefore it describes the causal effects of those distributions on actor behavior. For example, a powerful actor with a preference for relative gains in a unipolar system is likely to behave one way; a weak actor with a preference for absolute gains is likely to behave differently. Power structure theory elucidates how all of this works.

4. PST unifies neorealism and neoliberalism.

Neorealism and neoliberalism have for decades been the two predominant theories in IR. Neorealism views the international realm primarily as a struggle for power. Neoliberalism emphasizes cooperative interactions among states and the significance of international institutions. In the 1980s, attempts were made to unify these two theories under the framework of game theory and rational choice. However, this much sought-after “neo-neo synthesis” did not come to fruition.

Power structure theory supplies two ingredients necessary for that synthesis, ingredients that were missing in the 1980s. First, it offers a conception of power as dynamic flow (points 1 and 2 above). Second, it accommodates preferences for absolute and relative gains based on the distribution of power (point 3). These components are the missing links that connect complex interdependence (neoliberalism) and concerns for the distribution of power (neorealism) into a deeper framework. By combining these pieces, the phenomena described by neorealism and neoliberalism emerge as special cases of power structure theory.

The full rationale behind this unification requires some explanation, and you can find more details here.

5. PST reconciles structure and agency.

Which has more of an effect on outcomes in the international system: the agents within it or the structure of the system itself? Put another way: To what extent do actors determine the system, as opposed to the system determining them? This friction between structure and agency is another theoretical tension in IR.

In power structure theory, this tension does not exist. The behavior of agents is what forms the structure; and the structure is what agents react to. Thestructure part of a power structure is the relationships among the actors. Each relationship is a stream of transactions, such as commercial transactions between trade partners or military attacks between countries at war. The overall structure is created by the sum total of these complex interactions among the various actors. How they choose to act — that is, how they adjust their existing relationships — is done in reaction to everyone else’s relationships and to the distribution of power. So agents continually create the structure, which in turn alters their incentives to undertake various actions in the future. The tension between structure and agency dissolves away.

6. PST applies to state, intrastate, and transnational actors.

Traditionally, IR theory applied only to states, but it was eventually realized that intrastate and transnational actors were also relevant and needed to be accounted for. Few models in IR apply broadly to state, intrastate, andtransnational actors. However, power structure theory does.

A power structure describes relationships among generic actors, be they countries, institutions, intergovernmental organizations, criminal gangs, city-states, or individuals. Each node in a power structure is a simplification that can often be decomposed into another power structure unto itself — meaning that power structures can be nested within each other. For example, if the countries of the world constitute a power structure with ~195 actors, each of those is also its own self-contained national power structure made up of government agencies, corporations, influential individuals, etc. Power structure theory is a theory about power, and since political power is relevant at various levels of social organization, the theory is generally applicable. One benefit of this generality is that PST helps connect power struggles occurring within states to their external behavior towards other states, and vice versa. Essentially, PST models each nation state “billiard ball” as a collection of smaller billiard balls that follow the same operational principles.

7. PST provides IR with an axiomatic foundation.

Scientific theories, including in the social sciences, should ideally state the assumptions upon which they are based. These assumptions should be simple and clear, and there should be as few of them as necessary. They should be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. And they should be capable of describing or explaining a wide variety of phenomena despite their minimalist nature.

Power structure theory provides just such an axiomatic foundation. It is based on a minimal set of principles upon which a variety of other conclusions can be drawn. Some examples of these axioms (stated informally) are: when actors cooperate, they get stronger; when actors fight, they get weaker; actors prefer some combination of absolute and relative power; and actors engage in ongoing interaction. There are a handful of other axioms (which I’m omitting so as not to overly confuse you) that together serve as the starting point for a comprehensive theory. By explicitly stating these assumptions, power structure theory wrings out as much ambiguity as it can from the conclusions it draws. The clearer the inputs, the clearer the outputs.

8. PST is fundamentally quantitative.

In addition to being axiomatic, it’s a bonus when a scientific theory is quantitative in nature. When we can not only say that A causes B, but that A causes B to a specific degree, or at a specific rate, then we have a framework that can output precise answers to precise questions.

The axioms of power structure theory are quantitative in nature. They don’t just say how things change; they can be parameterized to specify how muchthose things change. In fact, the core of power structure theory boils down to three simple mathematical equations. Not only is this intellectually satisfying, but it also enables us to calculate and model the way power structures can change over time by creating computational simulations of this time evolution, and to test whether the models align with reality. It also means that we can formalize phenomena like the balance of power, empire, instability, Graham Allison’s Thucydides Traps, David Lake’s theory of hierarchies, the loss of strength gradient, Lanchester’s laws, polarity, and the multiple logics of anarchy (my apologies to nontechnical readers for this sentence).

This doesn’t mean that we can predict the future. Power structure theory is not predictive per se. But the simulations can help us understand tendencies and likely outcomes in the system, even if they can’t tell us exactly what is going to happen in a given situation. If PST did claim to predict such things, it wouldn’t be believable, because politics is inherently unpredictable.

9. PST gives us a way to rank each state’s position in the system.

Because power structure theory is axiomatic and quantitative, it allows us to come up with novel metrics that help us understand what’s happening in the system. One such metric is called PrinceRank, which is a network centrality measure that takes into account negative links (i.e. destructive relationships). Essentially, it tells us — numerically — how happy each actor is with its place within a given power structure.

This is the same power structure as the one shown above, but with each actor colored on a blue-green spectrum that indicates PrinceRank. Light green represents the most favorable position in the network, whereas dark blue represents the least.

PrinceRank allows us to rank power structures based on an actor’s preferences and as a result it can help us see which actions or “foreign policies” would be most beneficial for that actor to take. This means that it can be used to explore the possible choices that each actor has when they play against each other in a simulated “game” of international politics.

10. PST explains why politics consists of perpetual change.

Political systems at every level — global, national, local — are constantly changing. Some actors rise to power and others fall in the continual turbulence of human events. Power structure theory helps us understand why this turbulence will never end.

Power structures are in perpetual disequilibrium. If they are ever static, they do not remain so for long. Even when the relationships in a power structure remain unchanged, the power levels of the actors fluctuate due to the flow of power across the network. And of course, relationships do not remain static, because there is always someone who wants to improve their position by forming a new alliance or fomenting conflict. Even unequal, hierarchical structures like empires and authoritarian regimes are in perpetual flux. Though these structures are relatively durable and can persist for some time, there are actors within them that nonetheless continually challenge the status quo in order to seek incremental gains in power. In short, power structures help explain why, in politics, change is the only constant.

11. PST helps crystallize what actors construct when they engage in “social construction.”

Constructivism is another major theory of international relations, along with neorealism and neoliberalism. The thrust of it is that the key structures of the international system are socially constructed through shared ideas, norms, identities, and beliefs, rather than being solely determined by material forces.

Power structures are, in part, socially constructed. While they are objectively real, they are so large and complex that no one knows them in their entirety, and hence it is necessary for actors to form mental simplifications. Everyone then acts based upon their subjective understanding, as if it’s a board game night where no one can see the actual board. How these simplified understandings are formed is part of the game of politics: convincing others about who has too much power, who has too little, who’s abusing it, and what should be done with the power at one’s disposal. In other words, significant aspects of those shared ideas, norms, identities, and beliefs can be conceptualized in the vernacular of power structures, because fundamentally they are about some struggle for power.

12. PST provides a launch point for the development of normative theory.

Power structure theory provides a basis for the development of a normative theory of international politics. PST is a descriptive theory. It describes what can and may happen, not what should happen. What should or ought to happen falls into the realm of ethics, and it’s important to try to separate such normative theories from descriptive ones, for clarity’s sake. But normative theories should start by taking the world as it is, and if at the most fundamental level the international system is best represented as a power structure, then normative theories should use PST as a starting point. They should build upon the assumptions of PST and use its conceptual language when developing arguments about how actors in the system ought to act.

Hopefully, I’ve opened your mind to the possibility that power structure theory can tie together a variety of existing ideas in IR by offering a solid foundation upon which they can rest. PST doesn’t necessarily conflict with mainstream theory. To the contrary, I believe that it shows how existing ideas are interconnected via a deeper conceptual substrate — a three dimensional object that has been casting a bunch of familiar theoretical shadows.

There’s a lot more that can be said about each of the arguments above. If you’re interested in learning more, most of these themes are discussed in greater detail in my book, Power Structures in International Politics (2023). Also feel free to message me directly if you feel so inclined.

Drezner, D. (2020). Power and International Relations: a Temporal View. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 29-52.https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120969800.