Amal-Tikva: Resilience and Updates from the Field

Amal-Tikva continues to adapt to the volatile realities of the region, redirecting resources and supporting peacebuilding organizations with resilience and focus. When the Leading through Trauma retreat was cancelled due to the Israel–Iran war, the budget was reallocated to provide one-on-one psychological support for NGO leaders in partnership with the Headington Institute. This approach reflects the organization’s ability to sustain its mission even in times of upheaval.

Program Highlights

ATLI Emerging Leaders 2025: Sixteen Israeli and Palestinian grassroots and policy leaders have completed ten sessions with experts in peacebuilding and management. The cohort will travel to Belfast later this year for a study tour with ReThinking Conflict, while a reciprocal tour will take place in 2026.

Speakers Bureau: Nine peacebuilders participated in training and mentorship to develop skills in storytelling, audience engagement, and message delivery. The program concluded with a final event where participants presented to donors and peers, reflecting Amal-Tikva’s commitment to elevating peacebuilding voices.

Fieldbuilding360: Fifteen NGOs are currently taking part in the Fieldbuilding360 program. A recent donor panel enabled four organizations to present strategies and refine their theories of change with direct feedback from funders.

Partnership with B8 of Hope: Collaboration with B8 of Hope has focused on refining grant processes, deepening due diligence, and expanding the funding pipeline. The partnership demonstrates how shared values can strengthen the broader peacebuilding field.

Looking Ahead

An ATLI alumni retreat will take place in September in rural Italy, offering leadership and resilience training.

A new strategic planning workbook, developed with Hebrew University’s MA program in non-profit management under Dr. Nancy Strichman, will soon be available as part of Fieldbuilding360.

Amal-Tikva is expanding its team, with two new hires joining in August and September, and is currently recruiting for a Community Manager.

Amal-Tikva’s work illustrates how peacebuilding organizations are responding to a challenging environment with strategy, resilience, and impact. The organization continues to support leaders and NGOs in strengthening civil society engagement while adapting to rapidly changing realities.

Learn more here: https://www.amal-tikva.org

Meredith Rothbart

Meredith Rothbart is the Founder and CEO of Amal-Tikva, a collaborative initiative bringing together philanthropists, field experts, and organizations to strengthen civil society peacebuilding between Israelis and Palestinians. Since immigrating to Jerusalem in 2008, Meredith has dedicated her career to advancing dialogue, cooperation, and sustainable peace in the region.

She holds an MA in Community Development from Hebrew University and a BA in Politics, Philosophy and Economics from the University of Pittsburgh, and brings nearly 15 years of leadership experience with Israeli and Palestinian NGOs. Meredith previously served in the IDF Civil Administration, and her participation in an early leadership program for young Israelis and Palestinians inspired her lifelong commitment to peacebuilding.

Meredith has become an influential voice in the international policy and peacebuilding community. She has addressed the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, the White House, the Delegation of the European Union to Israel, and the United Nations Security Council, consistently advocating for the role of civil society in conflict transformation. She also serves on multiple advisory boards and was the founding curator of the Jerusalem Global Shapers Hub of the World Economic Forum.

In addition to her leadership at Amal-Tikva, Meredith is a strategic consultant, writer, and public speaker whose work has been widely recognized for advancing nuanced perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

She lives in Jerusalem with her husband and children, Shalva, Yishai, and Yona.

Oslo Scholars Program

The Oslo Scholars Program (OSP) offers undergraduates with demonstrated interest in human rights and international political issues an opportunity to attend the Oslo Freedom Forum in Norway and spend their summer working with some of the world’s leading human rights defenders and activists.

The Oslo Scholars Program was established in 2010 by Sherman Teichman in partnership with the Human Rights Foundation (HRF) and the Institute for Global Leadership at Tufts University, as HRF presented an ideal platform to engage new generations of human rights defenders and scholars.

How It All Began - Sherman Teichman, Founder of Oslo Scholars

My aspiration for the Oslo Scholars was to promote and ensure a strong intergenerational interaction and a robust continuity of new generations of young, informed human rights activists, derived from my own experience as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University, where I was active with Amnesty International in 1963-65 as part of its AI’s inaugural efforts at internships. (It is amusing to me that AI, which to me was so important at Amnesty International, is now considered Artificial Intelligence, whereas the AI I knew was dedicated to compassionate humanistic activity to save wrongfully imprisoned individuals.) I had two wonderful mentors: Chester Wickwire, the University Chaplain, and Professor Hans W. Gatzke. Chester was a mentor to me in the civil rights movement, and Professor Gatzke taught me about the foreign and domestic policies of Nazi Germany and the horrors of war when I was still enrolled in the Marine Corps Platoon Leader Training ROTC program when I was an undergraduate.

I distinctly remember Hans’ full-length German Nazi Map of the sites of many of the 47,000 concentration and extermination camps. I was seduced by my aspiration to be a “Whiz Kid” Military Officer designing “Hearts and Minds” counter-insurgency programs in Vietnam, wonderfully debunked by Hans, and recorded in David Halberstam’s famous book The Best and the Brightest. I assigned this book in many of my university classes together with an extraordinary, too unrecognized book, The Nightingale Song. I had the great fortune to be able to honor Professor David Halberstam with my Institute’s Jean Mayer Award.

Wonderfully, many of my past and current Trebuchet interns (including Chloe Yau, first lower left) have fulfilled my aspirations and have become Oslo Scholars. I saw universities as superb homes where they could hone their intellectual and activist skills, and subsequently provide HRF’s human rights activists and honorees with important support, be it administrative, technological, legal, or design skills, and, in particular, research and computer capacity.

One of my senior research papers at JHU was on Kant’s categorical imperative and The Nuremberg Trial by Ernst von Weizsäcker, I had the amazing privledge to do some of my research at Columbia University’s Low Library, which at that point was one of the two repositories of the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials and critically had the opportunity to have an in depth afternoon interviewing Telford Taylor. One of my regrets was never interviewing William Shawcross, another brilliant scholarly author on Nuremberg and much else.

Oslo Scholars 2025 - Oslo Freedom Forum

Tufts University Oslo Scholars (Chloe lower left and Alejandro third upper right)

Mozambican opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane giving an opening speech

Student Narratives

Witnessing Courage, Renewing Purpose - Chloe Yau 25’ Oslo Scholar

Growing up in Hong Kong, I learned early on how fragile basic human rights can be. Conversations about press freedom or political dissent could not be had in public; imagining a future where those rights were secure seemed impossible. That changed when I attended the Oslo Freedom Forum. Under the theme Imagine, the Forum invited us to picture a world free from repression, and for me, it became a space where hearing powerful personal stories of struggle and resistance was inseparable from envisioning a better future—one imagined collectively, as a global community.

Upon arrival, I was struck by the diverse community of people, from artists, dissidents, activists, and politicians, the Forum dissolved distance. I met people whose names I had only read about in the news: Kim Yumi, who recounted the split-second decisions that saved her family during their escape from North Korea; Azza Abo Rebieh, a Syrian artist whose smuggled sketches gave fellow prisoners a fragment of dignity; and Sulaima Ishaq Elkhalifa Sharif, a Sudanese women’s rights activist and trauma specialist who has risked detention and her life to document sexual violence in the Sudanese conflict and to hold perpetrators accountable. Each story had a clarity and urgency that made it impossible to remain a passive listener.

The program’s breadth was striking. Discussions ranged from how authoritarian states hide wealth in global financial hubs, to the reach of digital surveillance, to the ways disinformation corrodes trust across borders. A panel on gender-based violence under authoritarian rule—featuring advocates from Libya, Tigray, Afghanistan, and Sudan—was especially difficult to hear, but necessary. Another, on labor abuses in international waters, resonated deeply with my interests in international law and environmental justice. Testimonies from Indonesian and Thai fishery workers exposed how human rights violations at sea often go unseen, and how urgently stronger protections are needed. Hearing such courageous personal accounts did more than inform me—they cemented my commitment to pursuing work at the intersection of migration, international law, and global justice.

What I took from these conversations was that every struggle, no matter how geographically distant, is part of the same global fight for dignity. Policies, institutions, and treaties matter—but so do the individual voices that put a human face on injustice.

For me, being an Oslo Scholar was not just about access to an extraordinary network. It was a moment of realignment. I left Oslo with a sharpened sense of purpose and a community that made the idea of a freer world feel less like a distant hope and more like a collective project I could contribute to.

Global Voices on Global Issues - Alejandro Alvarez 25’ Oslo Scholar

The theme of the 2025 Oslo Freedom Forum was Imagine, an invitation to picture a freer, more just world. But in truth, imagining the impact of this experience before arriving in Oslo was impossible. From the very first moment, surrounded by passionate activists, survivors, and advocates from around the globe, it was clear this wasn’t just a conference; it was a living space of resistance, courage, and transformation. The opening speeches set the tone: North Korean defector Kim Yumi recounted her family’s harrowing escape, a journey from complete state control to the dignity of personal choice. Mozambican opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane shared how, despite systemic repression, he continues to advocate for democracy and truth in his country. Syrian artist Azza Abo Rebieh spoke of how her art, secretly sketched while imprisoned, became a lifeline for herself and fellow inmates under the Assad regime. Each story was personal, painful, and powerful, and reminded us that the fight for freedom is never theoretical.

What struck me most about the forum was its truly international scope. It didn’t limit itself to Western issues or familiar headlines. Instead, it offered a platform for voices from every corner of the world, inviting us to engage with stories and struggles we might otherwise never encounter. One panel explored Hong Kong’s evolving role as a financial haven for authoritarian regimes. Another examined the growing influence of China and Russia in Africa, unpacking how resource extraction and political interference have reshaped governance across the continent. These panels didn’t just inform but rather pushed us to question how power operates globally, and how international solidarity must be redefined in the 21st century.

As someone deeply passionate about Latin American politics, my favorite panel was “Venezuela: A Challenge for Democratic Solidarity in Latin America.” The lineup was striking: Juan José Matarí, President of Spain’s Ibero-American Affairs Committee; Ambassador Tomás Pascual from Chile’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Georgetown professor and OAS advisor Hector Schamis; and Ana Corina Sosa, daughter of opposition leader María Corina Machado. Together, they tackled the consequences of Maduro’s electoral fraud, the regional migration crisis, and the disappointing silence of many international actors. They also drew vital links to the situations in Cuba and Nicaragua and analyzed how global powers like China are reshaping the hemisphere’s political landscape. It was honest, layered, and long overdue.

Being an Oslo Scholar was far more than an academic or professional milestone. I left the Forum with a renewed sense of purpose and a deeper commitment to fighting for justice, both in Latin America and beyond. This experience marked the beginning of a summer devoted to social advocacy through the Human Rights Foundation’s affiliated initiatives, but it also marked something more profound: a reminder that change starts with listening and imagining that another world is possible.

Dry Lands, Deep Courage: Co-Resisting Water Apartheid in the Jordan Valley

Water scarcity in the West Bank has long been a central issue, but for many Palestinian farming families, the challenge is not just access—it is survival. Farmers in areas such as Bardala in the northern Jordan Valley report that their irrigation systems are often vandalized, their water tanks destroyed, and their crops trampled. Daily struggles include making multiple trips through checkpoints to secure water, often spending entire days just to bring it home.

At a recent gathering, one farmer described the risks of tending his fields under threat of violence, while another, Muhamed, shared that each morning he says farewell to his family as though it could be the last time. Activists from Combatants for Peace (CfP), both Palestinian and Israeli, have been present in these communities, standing alongside farmers to help ensure they are not left alone.

CfP’s commitment extends beyond protection. On August 15, students from CfP’s Palestinian Freedom School delivered two water tanks to families in Al-Walajeh, supporting their resilience against water shortages. Yet, even CfP’s own Palestinian organizers face similar deprivation, with some homes receiving little or no water despite scheduled supply days.

To spotlight these realities and the ongoing grassroots resistance, CfP will host an online seminar:

Dry Lands, Deep Courage: Co-Resisting Water Apartheid in the Jordan Valley

Wednesday, August 20, 2025

1:00–2:15 PM ET

Participants will hear directly from CfP activists about their work with Palestinian farming communities and the broader campaign for water justice.

Register here to attend the event and learn more about the intersection of daily survival, solidarity, and resistance.

Michael Poulshock on Power Structures

Michael Poulshock, of our community.

How Power Structures Advance IR Theory

Twelve potential upgrades to the theory of international relations

JUL 31

How should we understand international politics? Like any social science, the field of international relations (IR) is a bundle of models that attempt to answer that question. And as in any academic field, there will always be some models that are in tension with each other and don’t quite snap together they way we hope they would. Science is, after all, an ongoing process. But in international relations, there seems to be a distinct sense that the discipline lacks a unifying framework for solving the puzzles that are within its purview to address. Its dominant theories have not been reconciled and there is no consensus on the definition of its most fundamental concept.

As an analogy, imagine that each theory is a shape. Some theorists might see one shape and describe the phenomena of international politics as a rectangle. Another group of scholars might see a different shape and say, “No, it’s a circle.” A third group might be convinced that a triangle is the best explanation. The shapes are a bit hazy, but nonetheless there’s an accumulation of evidence in favor of each one and the debates ensue.

Yet it may be that there’s another perspective from which we can view the situation that offers a more coherent explanation. Perhaps what we’ve actually been looking at are shadows cast by some unexpected three dimensional object, rotated around in different ways. From one angle, the object creates a rectangular shadow; from another, a circular one; and from third, a triangle. From this new vantage point, some of our existing models may simply turn out to be special cases projected down from a higher dimensional idea that is somehow more fundamental.

A 3-dimensional object that casts rectangular, circular and triangular shadows.

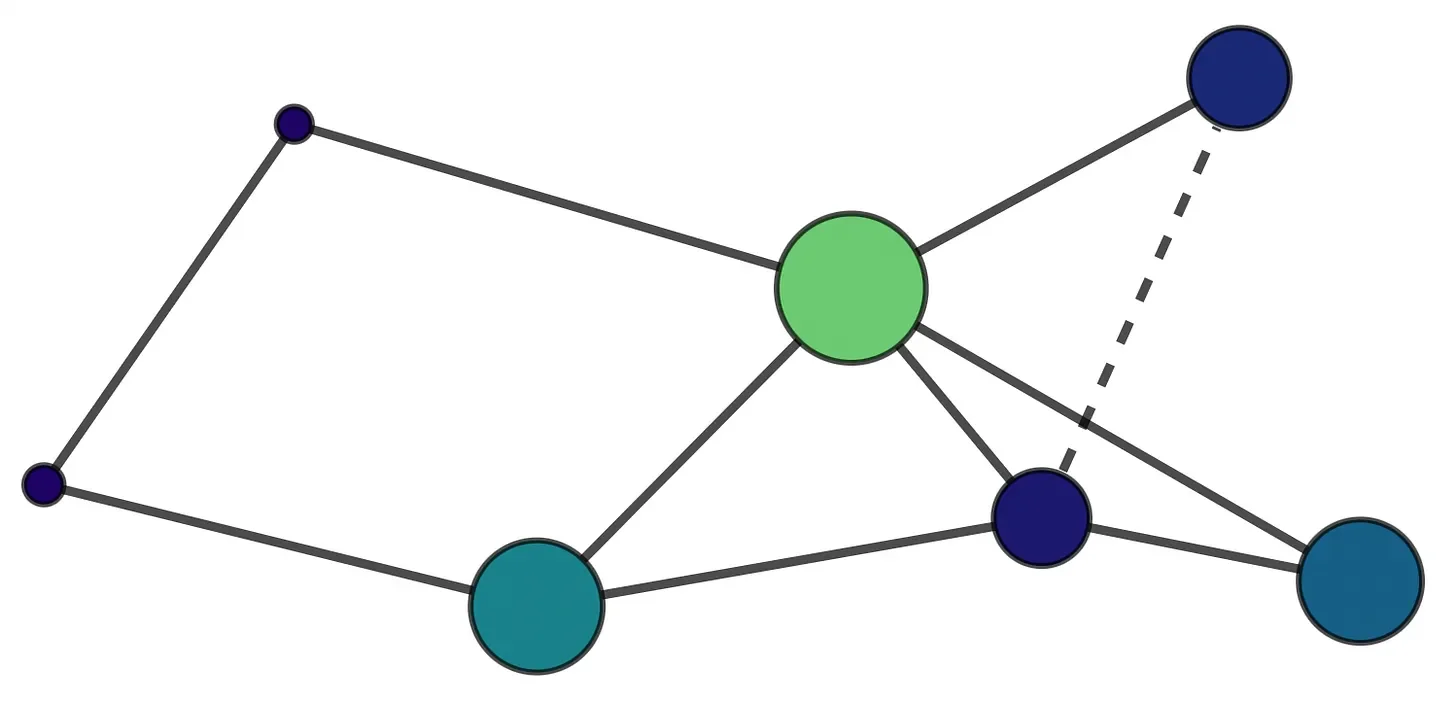

Power structure theory is that deeper idea, and in this post I’m going to give you twelve reasons why I believe that it can help us unify international relations theory. For the sake of space, I’m not going to reiterate what power structure theory is; a primer can be found here. The diagram below is illustrative of the basic idea, and I’ll elaborate other key aspects of it as we go along.

A power structure is a system of relationships among political actors with varying levels of strength. More powerful actors are depicted as larger circles. Solid lines indicate cooperative relationships; dashed lines represent conflict. Power structures evolve over time: actors who cooperate get stronger, actors who fight get weaker, and relationships continually change.

Since I’ll be referring to academic concepts, some of my points may seem a bit obscure if you’re a nonspecialist. I’ll do my best to simplify and contextualize them. Conversely, if you’re an IR scholar, you may be unimpressed by my lack of nuance or my inadequate citations to the literature. In the end, it may be that this essay doesn’t quite work for anyone: it may be too technical for general readers and too sloppy for academic ones. What can I say? That’s my niche.

Each of the points below could probably be an essay unto itself, and maybe I’ll expand upon some of them in future posts. For now, my goal is just to show you that power structure theory — which I’ll abbreviate as PST — has the potential to draw together a variety of loose ends in our current understanding of international politics. Here are twelve ways it might do that.

1. PST defines the central, unresolved concept in IR.

As Daniel Drezner wrote a few years ago, “International relations scholars do not agree about much, but they are certain about two facts: power is the defining concept of the discipline, and there is no consensus about what that concept means.”¹ This may at first seem like an astonishing admission and a bit of an embarrassment. However, it can take a long time for very simple things to be understood correctly. Consider physics, where it took two millennia — from Aristotle to Newton — until force and mass were properly defined. Or negative numbers, which required a thousand years before mathematicians fully accepted them. Many ideas that are now taught to elementary school students took centuries to figure out. Political power might be in this category.

We understand power in an experiential, biological way, and perhaps that’s why it’s hard to conceive of it at the appropriate level of abstraction. Power structure theory defines power as “an actor’s ability to affect the amount of power that other actors have.” It’s a sparse and circular definition, and for those reasons it is counterintuitive and controversial. However, it describes phenomena that are at the heart of power politics (see below), and therefore any idiosyncrasies of the definition are justified by the success of its ultimate results. In this way, PST plugs the most glaring hole in international relations theory — its central, unresolved concept.

2. PST describes processes of change in the international system.

PST describes the international system as a power structure — a system of relationships among actors with varying degrees of power. Power structures are not static, and power structure theory is based on assumptions about how these structures change over time. PST therefore provides a descriptive account of the dynamics of international politics.

One process of change is due to the relationships among states (or other actors): cooperation tends to make them stronger, whereas conflict weakens them — and this can be visualized as a flow of power in the network. But actors also change their relationships with each other in reaction to their place in the structure. The dynamics of the system are a feedback loop between these two processes, and result in familiar patterns like hierarchy formation, the balance of power, divide and rule tactics, and defensive alliances. Existing IR models endeavor to establish causal links between various phenomena. However, PST goes further and provides a way to express power struggles in an abstract model that accounts for the time evolution of the system.

3. PST provides a conception of utility that balances absolute and relative gains.

What do actors in a power structure want? They want to accumulate more power in absolute terms, so they can be stronger. But they also care about how much power they have relative to other actors, so they can avoid being dominated. Their satisfaction or utility within a power structure is based on their preference for absolute versus relative gains in power.

How actors strike this balance has a big effect on how they behave. Actors who have a stronger preference for absolute power will be more willing to cooperate for mutual gain, because they are not threatened by the fact that someone else is getting stronger. In contrast, actors who prefer relative gains tend to behave aggressively towards other actors. They are more prone to using violence to reduce the power of rivals to a more manageable level, weakening them to the point where they are submissive and unthreatening.

This conception of utility connects preferences for absolute and relative gains to the distribution of power — that is, to the amount of power that each actor in the system has. It explains the incentives that actors face when confronted with different distributions of power, and therefore it describes the causal effects of those distributions on actor behavior. For example, a powerful actor with a preference for relative gains in a unipolar system is likely to behave one way; a weak actor with a preference for absolute gains is likely to behave differently. Power structure theory elucidates how all of this works.

4. PST unifies neorealism and neoliberalism.

Neorealism and neoliberalism have for decades been the two predominant theories in IR. Neorealism views the international realm primarily as a struggle for power. Neoliberalism emphasizes cooperative interactions among states and the significance of international institutions. In the 1980s, attempts were made to unify these two theories under the framework of game theory and rational choice. However, this much sought-after “neo-neo synthesis” did not come to fruition.

Power structure theory supplies two ingredients necessary for that synthesis, ingredients that were missing in the 1980s. First, it offers a conception of power as dynamic flow (points 1 and 2 above). Second, it accommodates preferences for absolute and relative gains based on the distribution of power (point 3). These components are the missing links that connect complex interdependence (neoliberalism) and concerns for the distribution of power (neorealism) into a deeper framework. By combining these pieces, the phenomena described by neorealism and neoliberalism emerge as special cases of power structure theory.

The full rationale behind this unification requires some explanation, and you can find more details here.

5. PST reconciles structure and agency.

Which has more of an effect on outcomes in the international system: the agents within it or the structure of the system itself? Put another way: To what extent do actors determine the system, as opposed to the system determining them? This friction between structure and agency is another theoretical tension in IR.

In power structure theory, this tension does not exist. The behavior of agents is what forms the structure; and the structure is what agents react to. Thestructure part of a power structure is the relationships among the actors. Each relationship is a stream of transactions, such as commercial transactions between trade partners or military attacks between countries at war. The overall structure is created by the sum total of these complex interactions among the various actors. How they choose to act — that is, how they adjust their existing relationships — is done in reaction to everyone else’s relationships and to the distribution of power. So agents continually create the structure, which in turn alters their incentives to undertake various actions in the future. The tension between structure and agency dissolves away.

6. PST applies to state, intrastate, and transnational actors.

Traditionally, IR theory applied only to states, but it was eventually realized that intrastate and transnational actors were also relevant and needed to be accounted for. Few models in IR apply broadly to state, intrastate, andtransnational actors. However, power structure theory does.

A power structure describes relationships among generic actors, be they countries, institutions, intergovernmental organizations, criminal gangs, city-states, or individuals. Each node in a power structure is a simplification that can often be decomposed into another power structure unto itself — meaning that power structures can be nested within each other. For example, if the countries of the world constitute a power structure with ~195 actors, each of those is also its own self-contained national power structure made up of government agencies, corporations, influential individuals, etc. Power structure theory is a theory about power, and since political power is relevant at various levels of social organization, the theory is generally applicable. One benefit of this generality is that PST helps connect power struggles occurring within states to their external behavior towards other states, and vice versa. Essentially, PST models each nation state “billiard ball” as a collection of smaller billiard balls that follow the same operational principles.

7. PST provides IR with an axiomatic foundation.

Scientific theories, including in the social sciences, should ideally state the assumptions upon which they are based. These assumptions should be simple and clear, and there should be as few of them as necessary. They should be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. And they should be capable of describing or explaining a wide variety of phenomena despite their minimalist nature.

Power structure theory provides just such an axiomatic foundation. It is based on a minimal set of principles upon which a variety of other conclusions can be drawn. Some examples of these axioms (stated informally) are: when actors cooperate, they get stronger; when actors fight, they get weaker; actors prefer some combination of absolute and relative power; and actors engage in ongoing interaction. There are a handful of other axioms (which I’m omitting so as not to overly confuse you) that together serve as the starting point for a comprehensive theory. By explicitly stating these assumptions, power structure theory wrings out as much ambiguity as it can from the conclusions it draws. The clearer the inputs, the clearer the outputs.

8. PST is fundamentally quantitative.

In addition to being axiomatic, it’s a bonus when a scientific theory is quantitative in nature. When we can not only say that A causes B, but that A causes B to a specific degree, or at a specific rate, then we have a framework that can output precise answers to precise questions.

The axioms of power structure theory are quantitative in nature. They don’t just say how things change; they can be parameterized to specify how muchthose things change. In fact, the core of power structure theory boils down to three simple mathematical equations. Not only is this intellectually satisfying, but it also enables us to calculate and model the way power structures can change over time by creating computational simulations of this time evolution, and to test whether the models align with reality. It also means that we can formalize phenomena like the balance of power, empire, instability, Graham Allison’s Thucydides Traps, David Lake’s theory of hierarchies, the loss of strength gradient, Lanchester’s laws, polarity, and the multiple logics of anarchy (my apologies to nontechnical readers for this sentence).

This doesn’t mean that we can predict the future. Power structure theory is not predictive per se. But the simulations can help us understand tendencies and likely outcomes in the system, even if they can’t tell us exactly what is going to happen in a given situation. If PST did claim to predict such things, it wouldn’t be believable, because politics is inherently unpredictable.

9. PST gives us a way to rank each state’s position in the system.

Because power structure theory is axiomatic and quantitative, it allows us to come up with novel metrics that help us understand what’s happening in the system. One such metric is called PrinceRank, which is a network centrality measure that takes into account negative links (i.e. destructive relationships). Essentially, it tells us — numerically — how happy each actor is with its place within a given power structure.

This is the same power structure as the one shown above, but with each actor colored on a blue-green spectrum that indicates PrinceRank. Light green represents the most favorable position in the network, whereas dark blue represents the least.

PrinceRank allows us to rank power structures based on an actor’s preferences and as a result it can help us see which actions or “foreign policies” would be most beneficial for that actor to take. This means that it can be used to explore the possible choices that each actor has when they play against each other in a simulated “game” of international politics.

10. PST explains why politics consists of perpetual change.

Political systems at every level — global, national, local — are constantly changing. Some actors rise to power and others fall in the continual turbulence of human events. Power structure theory helps us understand why this turbulence will never end.

Power structures are in perpetual disequilibrium. If they are ever static, they do not remain so for long. Even when the relationships in a power structure remain unchanged, the power levels of the actors fluctuate due to the flow of power across the network. And of course, relationships do not remain static, because there is always someone who wants to improve their position by forming a new alliance or fomenting conflict. Even unequal, hierarchical structures like empires and authoritarian regimes are in perpetual flux. Though these structures are relatively durable and can persist for some time, there are actors within them that nonetheless continually challenge the status quo in order to seek incremental gains in power. In short, power structures help explain why, in politics, change is the only constant.

11. PST helps crystallize what actors construct when they engage in “social construction.”

Constructivism is another major theory of international relations, along with neorealism and neoliberalism. The thrust of it is that the key structures of the international system are socially constructed through shared ideas, norms, identities, and beliefs, rather than being solely determined by material forces.

Power structures are, in part, socially constructed. While they are objectively real, they are so large and complex that no one knows them in their entirety, and hence it is necessary for actors to form mental simplifications. Everyone then acts based upon their subjective understanding, as if it’s a board game night where no one can see the actual board. How these simplified understandings are formed is part of the game of politics: convincing others about who has too much power, who has too little, who’s abusing it, and what should be done with the power at one’s disposal. In other words, significant aspects of those shared ideas, norms, identities, and beliefs can be conceptualized in the vernacular of power structures, because fundamentally they are about some struggle for power.

12. PST provides a launch point for the development of normative theory.

Power structure theory provides a basis for the development of a normative theory of international politics. PST is a descriptive theory. It describes what can and may happen, not what should happen. What should or ought to happen falls into the realm of ethics, and it’s important to try to separate such normative theories from descriptive ones, for clarity’s sake. But normative theories should start by taking the world as it is, and if at the most fundamental level the international system is best represented as a power structure, then normative theories should use PST as a starting point. They should build upon the assumptions of PST and use its conceptual language when developing arguments about how actors in the system ought to act.

Hopefully, I’ve opened your mind to the possibility that power structure theory can tie together a variety of existing ideas in IR by offering a solid foundation upon which they can rest. PST doesn’t necessarily conflict with mainstream theory. To the contrary, I believe that it shows how existing ideas are interconnected via a deeper conceptual substrate — a three dimensional object that has been casting a bunch of familiar theoretical shadows.

There’s a lot more that can be said about each of the arguments above. If you’re interested in learning more, most of these themes are discussed in greater detail in my book, Power Structures in International Politics (2023). Also feel free to message me directly if you feel so inclined.

Drezner, D. (2020). Power and International Relations: a Temporal View. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 29-52.https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120969800.

Podcasts by Mukesh Kapila

These extraordinary podcasts are coming to you from Mukesh Kapila:

Thirty years after the Srebrenica genocide, what has been learnt? Especially for our age of endless wars. That is the topic for my last opinion piece.

Also, my new "Fading Causes" podcast is getting established. In the latest Episode, I talk to model Noella Coursaris about the power of loss that drives the passion to make a difference to others. In the earlier episode, I question Major General James Cowan on being good soldiers in bad wars.

You can also access these items via my website. You can contact me HERE. Your suggestions and comments are always welcome.

The complex legacy of Srebrenica and why today's wars never seem to end.

24 July 2025

When there is no universal settled truth, there is no final peace either

Episode 4 Fading Causes Podcast: model Noella Coursaris

29 July 2025

Can personal passion make a lasting difference?

Episode 3 Fading Causes Podcast: Major General James Cowan

22 July 2025

Léo Stern - France’s Recognition of the State of Palestine

A note, composed by Léo Stern , of our community.

C4ADS launches Horizons

I have had the fortune of working with C4ADS in my instruction at various universities. Several of my wonderful alumni, including Jack Margolin, have been directors of research at C4ADS. I urge that its platform be utilized: Horizons is a wonderful oppurtunity.

From uncovering illicit networks to tracing financial flows, the strongest investigations rely on fast, reliable access to publicly available information. But the software solutions that help uncover connections within this data have not evolved to meet the complexity of modern investigations.

So C4ADS built their own: Horizons.

John Shattuck

Professor John Shattuck is a distinguished international legal scholar, diplomat, and human rights leader with a career spanning over four decades. His professional journey began in the early 1970s as a law clerk in New York, before transitioning into academia as a visiting lecturer at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Politics. He later served as National Staff Counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), where he worked on key federal court cases, including the successful challenge to Nixon's warrantless wiretapping program, Halperin v. Kissinger. In the late 1970s, Shattuck was appointed the director of the ACLU’s Washington office, where he led lobbying efforts on civil rights and liberties during the Carter and Reagan administrations.

Shattuck’s academic and diplomatic careers are equally distinguished. In 1986, he returned to academia at Harvard University as Vice President for Government, Community, and Public Affairs, while also teaching law courses at Harvard Law School. His involvement with the Kennedy School of Government further strengthened his role in public policy. He was later appointed by President Bill Clinton as Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, where he played a pivotal role in the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, and negotiated the Dayton Peace Agreement that ended the war in Bosnia. Shattuck also served as U.S. Ambassador to the Czech Republic, where he helped modernize the country’s legal system and supported civic education programs.

In 2001, Shattuck became the CEO of the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, where he oversaw the digitization of historical records and significantly increased the foundation’s endowment. From 2009 to 2016, he served as the President and Rector of Central European University (CEU), transforming the institution into a globally recognized center for graduate education. Under his leadership, CEU expanded its interdisciplinary programs, launched the School of Public Policy, and created the Roma Access Programs, which are unique graduate preparation initiatives for Roma students. Shattuck also led the university through significant growth in research funding and faculty recruitment.

Shattuck’s legacy at CEU continues through the Shattuck Center on Conflict, Negotiation, and Recovery, named in his honor after his retirement. In addition to his work at CEU, Shattuck is currently a Professor of Practice at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a Senior Fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School Center for Human Rights Policy. He is a frequent author of articles on international relations, human rights, civil liberties, and public service, and has written three books, including Freedom on Fire, a study of the international response to genocide in the 1990s.

A graduate of Yale Law School, Shattuck has received multiple honorary degrees and prestigious awards, including the Yale Law School Public Service Award, the Ambassador’s Award from the American Bar Association, and the Jean Mayer Global Citizenship Award from Tufts University. He has also been elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Shattuck’s extensive career in government service, academia, and diplomacy, along with his lifelong commitment to advancing human rights and civil liberties, has left an indelible mark on international relations and higher education. He continues to contribute to the field through his academic roles and advocacy for democracy, human rights, and the protection of privacy.

John has been a wonderful friend for decades. As an educator and teacher I can say with humility that he far surpasses me. I know this because my son, Nathaniel, as a Tufts undergraduate, took a seminar on US foreign policy at the John F. Kennedy Center in Boston, which John directed. One of the sessions was a simulation about the Cuban Missile Crisis. Nathaniel was given the role playing position of Kennedy’s advisor Theodore Sorenson, which he found to be one of the best days of his academic career. He prepared rigorously for the idea that he would be in a replica room of the President, with others that were making the decision whether or not to bomb Cuba. (Nathaniel and I agreed that he would not take any of my classes, it could have been too stressful for both of us :)) John participated in many of my forums, always provocatively and thoughtfully. He could create tremendous excitement in a very soft-spoken but erudite manner. I had the privilege and honor of working with John and our close friend Richard Balzer, on the memorial Petra Foundation, in honor of John’s first wife, an extraordinary effort to acknowledge remarkable heroes of marginalized communities, ranging from anti-death penalty activists to indigenous rights activists.

John was one of my first interviewees when I worked for the Council of European Studies and its publication EuropeNow. I interviewed him on the future of democracy and threats to democracy. Then, as always, he is a prescient thinker and knew firsthand of the threat when the Hungarian authoritarian prime minister Orbán sadly succeeded in forcing the relocation of the George Soros founded Central European University. John last spoke for me when I secured him as the keynote speaker for “Democracy on the Precipice”, an EPIIC “revival” after 10 years of my absence in 2025. Attending his keynote was a sort of homecoming for me. He began by acknowledging my impact.

John Shattuck and I served together as Senior fellows at the Carr centre for human rights at Harvard.

James Lindsay

James M. Lindsay is the Mary and David Boies distinguished senior fellow in U.S. foreign policy and director of Fellowship Affairs at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). His work at the Council focuses on U.S. national security policy, the U.S. foreign policymaking process, the domestic politics of U.S. foreign policy.

From 2009 to 2024, Lindsay was senior vice president, director of studies, and Maurice R. Greenberg chair at CFR, where he oversaw the work of the more than six dozen fellows in the David Rockefeller Studies Program as well as CFR’s fourteen fellowship programs. Before returning to CFR in 2009, Lindsay was the inaugural director of the Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law at the University of Texas at Austin, where he held the Tom Slick chair for international affairs at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. From 2003 to 2006, he was vice president, director of studies, and Maurice R. Greenberg chair at CFR. He previously served as deputy director and senior fellow in the foreign policy studies program at the Brookings Institution. From 1987 until 1999, he was a professor of political science at the University of Iowa.

From 1996 to 1997, Lindsay served as director for global issues and multilateral affairs on the staff of the National Security Council. He has also served as a consultant to the United States Commission on National Security/21st Century (Hart-Rudman Commission) and as a staff expert for the United States Institute of Peace's congressionally mandated Task Force on the United Nations.

Lindsay has written widely on various aspects of American foreign policy and international relations. His most recent book, co-authored with Ivo H. Daalder, is The Empty Throne: America’s Abdication of Global Leadership. His previous book with Ambassador Daalder, America Unbound: The Bush Revolution in Foreign Policy, was awarded the 2003 Lionel Gelber Prize, named a finalist for the Arthur S. Ross Book Award, and selected as a top book of 2003 by The Economist. Lindsay’s other books include Agenda for the Nation (with Henry J. Aaron and Pietro S. Nivola), which was named an "Outstanding Academic Book of 2004" by Choice Magazine, and Congress and the Politics of U.S. Foreign Policy. He has also contributed articles to many major newspapers and magazines, including Foreign Affairs, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times. He writes the blog The Water's Edge, which discusses the politics of American foreign policy and the domestic underpinnings of American global power. He also hosts the weekly podcast, The President’s Inbox.

Lindsay holds an AB in economics and political science with highest distinction and highest honors from the University of Michigan and an MA, MPhil, and PhD from Yale University. He has been a fellow at the Center for International Affairs and the Center for Science and International Affairs, both at Harvard University. He is a recipient of the Pew Faculty Fellowship in International Affairs and CFR International Affairs Fellowship. He is a member of CFR.

Lindsay was born and raised in Massachusetts and lives in Washington, DC.

Jim, in my mind, was one of the more perceptive and impactful thinkers about US foreign policy and had a powerful impact on my thinking about International Relations. He participated in several EPIIC symposia and helped me mentor individual students. He also was the person to whom I had the pleasure of nominating as Fellow for the Council of Foreign Relations.

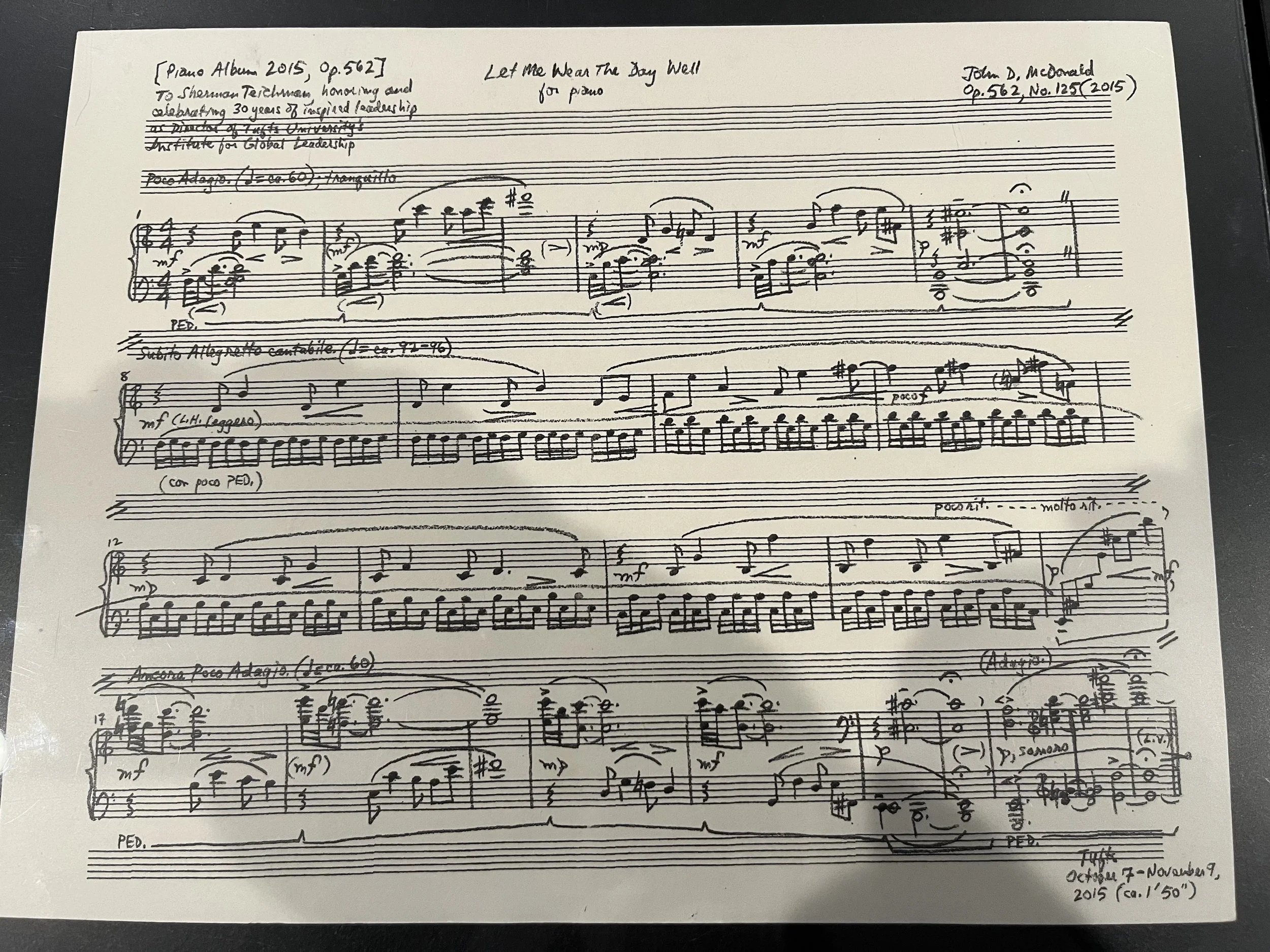

John McDonald

Recently described as “the New England master of the short piece,” John McDonald is a composer who tries to play the piano and a pianist who tries to compose. He received the 2009 Lillian and Joseph Leibner Award for Distinguished Teaching and Advising from Tufts University, and was named the 2007 MTNA-Shepherd Distinguished Composer of the Year by the Music Teachers National Association.

John McDonald is a Professor of Music at Tufts University, where he teaches composition, theory, and performance. His output concentrates on vocal, chamber, and solo instrumental works, and includes interdisciplinary experiments. Before going to Tufts in 1990, he taught at Boston University, Longy School of Music, M.I.T., and the Rivers Conservatory. He was the Music Teachers National Association Composer of the Year in 2007, and served as the Valentine Visiting Professor of Music at Amherst College in 2016-2017. Mr. McDonald was Music Department Chair at Tufts from 2000 to 2003. He has served as an Artistic Ambassador to Asia, and is on the advisory boards of American Composers Forum New England, Worldwide Concurrent Premieres, Inc., and several other cultural and academic organizations.

His recent and in-progress projects include Peace Process (for basset horn and piano), The Creatures’ Choir (an evening-long song cycle for voice and piano), Ways To Jump (a choral work concerning frogs, commissioned by Music Worcester), Piano Albums 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009 (collections of piano miniatures that attempt to chronicle some difficulties and joys of daily life through musical observation), Four Compositions for flute and piano, and a new work for saxophone and piano commissioned by the Massachusetts Music Teachers Association that responds to Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise. Pianist Andrew Rangell has just completed a recording (for Bridge Records; May 2009 release) of Mr. McDonald’s Meditation Before A Sonata: Dew Cloth, Dream Drapery, a piece which can function as a preamble to either of the monumental Charles Ives sonatas.

His recordings appear on the Albany, Archetype, Boston, Bridge, Capstone, Neuma, New Ariel, and New World labels, and he has concertized widely as composer and pianist. Recent performances at the Goethe Institut of Boston and at Tufts have been highly acclaimed. His solo piano recital of “Common Injustices” by twenty-five living composers prompted Richard Dyer of The Boston Globe to write “one can hardly imagine anyone else undertaking such a program, or playing it with such modest and unobtrusive but total musical and pianistic mastery.” Mr. McDonald has appeared with many ensembles and has maintained long-standing musical partnerships with soprano Karol Bennett, saxophonists Kenneth Radnofsky and Philipp Stäudlin, and several other prominent soloists. Since 2004 he has performed as pianist for The Mockingbird Trio (with Elizabeth Anker, contralto and Scott Woolweaver, viola).

John has been a close colleague and friend for decades during my time at Tufts University. He is an inspiring teacher and remarkable composer and musician. We collaborated in many ways. I am reminded of a fun prelude to a session during my EPIIC “Global Sports and Politics” year where his avant garde musical group, New Music Ensemble (NME) performed. I remember John playing his original music composition on a baby grand piano whose upraised piano cover was encased in netting with hundreds of ping-pong balls cascading as he played. John surprised me a number of times by composing and playing original compositions in my honor at different intervals in my 30-year career: my 20th, 25th and 30th anniversary.

There was also a delightful moment where he asked me to write a letter of recommendation for one of our common remarkable students, Rich Janoksky. Rich and his band performed at the EPIIC symposium “Future of Democracy” his original composition Habibi (Friend in Arabic) and then jammed with the jazz icon Chick Corea in an unforgettable improvisational concert.

Rich after receiving PhD at the University of Chicago in Ethnomusicology, and teaching at SOAS in London was applying for a tenure track faculty position at Tufts, his alma mater. Rich not only succeeded in gaining this position but is now the chairman of the music department at Tufts.

John also composed a beautiful piece in honor of an extraordinary mentor of mine, the renowned professor Stanley Hoffmann - the former head of the Center of European Studies at Harvard University, to whom I dedicated my last EPIIC year, “The Future of Europe”, in 2016.

Hariniy Gunaseelan

I am Hariniy Gunaseelan, you can call me Niy. I am a Data Science major, minoring in Philosophy. I am someone that has a deep curiosity for AI, large language models, and the ways technology intersects with art and philosophy, especially in light of the rise in AI. Besides being the lead singer (and the guitarist, occasionally) of my college band, “The Surrogates”, I am also an indie singer-songwriter, a poet, and an artist of multiple mediums. My wish is to sing for people that can’t speak or find acceptance and make art more accessible to anyone and everyone. I believe that the study and expression of what it is to be human is the greatest of all. My favourite things to do when it’s raining and I am stuck at home are drinking tea, watching video essays, crying about AOT (It’s an anime), creating art to add to my room, riling up the dogs, singing to my birds that will only listen to either Queen or classical baroque music, and talking to my mom. As the Red Team Lead in this project, I directed the research, writing, editorial layout, and managed social media coordination. This process stretched me in every direction; it was challenging, fulfilling, and taught me how powerful patience can be. It helped me grow not just as a researcher, but as a collaborator and creator. I have deep respect for my mentors and my peers that made this project come so far! I am looking forward to making our Youth Red Team a bigger voice in our world that speaks for responsible and ethical AI use.

Guo Feng (GAVIN)

Guo Feng (Gavin) is the CEO and Managing Director of Yulele, a company at the intersection of entertainment, culture, and social impact. He is currently spearheading the establishment of a Los Angeles–based division of Yulele in collaboration with Janet Yang, Chair of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and a long-standing advocate for Asian storytelling in Hollywood. Under his leadership, Yulele also manages top-tier talent across film, theatre, and classical music. One of the company’s featured pianists has performed at major venues globally, including Carnegie Hall, and on prominent occasions such as the G20 Summit.

Before launching Yulele, Gavin built a successful career in finance. He served as Executive Director at Morgan Stanley Asia Limited (Hong Kong) and as Director at Warburg Pincus, gaining extensive experience in global investment strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature and Economics from Peking University, and a Master’s in Management from Duke University.

Beyond business, Gavin has played an active role in public health and philanthropy. Yulele is the only “strategic partner” of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the entertainment sector, and three of its talents have been appointed as WHO Special Envoys of Public Health in China—a recognition of their contribution to initiatives in tobacco control and HIV containment in underserved regions. Gavin’s longstanding engagement with these issues has led to personal collaboration with WHO leadership, and their work has been widely reported across Chinese media.

In addition to his role at Yulele, Gavin serves as Executive Vice President of the Radio and Television Association of Hainan Province and is a member of the China Television Artists Association.

Learn more about his work here: http://www.yulele.com/

Sherman and Gavin first met during the Hong Kong and China Tufts Initiative for Leadership and International Perspective (TILIP program). Since then, Gavin has continued his journey at the intersection of business, creative media, and philanthropy, leading meaningful ventures while remaining deeply engaged in global impact and creative innovation.

J Barkath Aafreen

I’m J Barkath Aafreen, a thinker, a builder, a performer—and above all, a seeker. Curiosity has always been my guiding compass. It’s what drives me to question, explore, and engage with the world—not just on the surface, but in its deepest layers. Whether I’m decoding algorithms, dissecting global affairs, or diving into books on cognitive neuroscience; I’m in constant pursuit of understanding and impact.

Currently pursuing my B.Tech in Computer Science, I find myself deeply immersed in the evolving world of data science, AI/ML, and the philosophical underpinnings of generative AI. But for me, tech is never just about code. It’s about what lies beyond it—how we can transform raw data into meaningful experiences, how we can visualize knowledge in ways that change behavior, and how we can build intelligent agents that don’t just compute, but connect. My goal is to design not just functional AI, but expressive, human-centered systems that reflect empathy, emotion, and ethical awareness.

What excites me most is the integration of AI with fields like cognitive neuroscience and biology—the beautiful space where minds meet machines. The more I understand the brain and behavior, the more I realize the potential of designing AI that mirrors—not mimics—human thought. And it is in this interdisciplinary terrain that my curiosity blooms most.

But my journey isn’t confined to labs or lecture halls. As a district-level basketball player, I’ve learned the value of discipline, agility, and team spirit. The court has taught me how to handle pressure, how to adapt quickly, and how to lead with both clarity and composure. That spirit of resilience now powers my academic, technical, and creative pursuits.

Beyond STEM, I’ve long nurtured a passion for writing, reading, and storytelling. I believe that words are one of the most powerful tools we possess. I write not just to express—but to connect. My love for literature and communication fuels my content-creation efforts, especially those aimed at humanitarian causes, awareness campaigns, and youth engagement. I don’t just code, I communicate, and I don’t just inform, I inspire.

My interest in international relations and global systems was amplified after meeting Sherman—a mentor whose brilliance, humility, and mentorship sparked a new level of intellectual curiosity in me. That interaction wasn’t just a class discussion—it was a turning point. Since then, I’ve been motivated to explore how data science and diplomacy, security and software, ethics and engineering can all intersect to shape a more inclusive world.

Above all, I’m not just an academic or an enthusiast—I am a showman. I believe in the power of presence. Whether I’m performing on stage, networking in a room, or leading a project—I bring energy, emotion, and authenticity into everything I do because for me, learning is not a phase—it’s a lifestyle. Creation is not a skill—it’s a mindset. And curiosity? It’s not just what I have. It’s who I am.

Manaswini S

Hi! I'm Manaswini S, currently pursuing my B.Tech in Computer Science at Sai University. I believe that the pursuit of knowledge is a lifelong journey—one that began for me at a very young age. I have always been intrigued by the way the world functions and the various aspects associated with it. While curiosity usually kills the cat, for me, it has led to a wide set of interests—music, arts, history, mathematics, science (especially zoology and chemistry), philosophy, economics, current affairs, and more. Currently, coding is also becoming more of a genuine interest than just a degree requirement, and I’m exploring the wonders of the field.

Studies aside, I have been learning Indian Classical Music for nearly 12 years and have had the opportunity to perform in a few concerts. My love for music spans many genres—film scores, pop, hip-hop, folk, and beyond. Music has been such an integral part of my life that I honestly can’t imagine life without it. During my leisure time, I enjoy reading books (especially fiction), drawing, singing, browsing the internet, and traveling. Occasionally, I indulge in watching handpicked movies and series as well.

I strongly believe our efforts should not only nourish our own growth but also uplift others. While I haven't had the chance to learn directly under Sherman, I’m honored and excited to work with him and contribute significantly to The Trebuchet and its vibrant community. I'm looking forward to learning, collaborating, and growing together with everyone here.

Performing at the Thiruvaiyaru Thyagaraja Aradhana Festival, 2020

Abhinav Mohan Kumar

Rappelling at Gandikota

I am Abhinav Mohan Kumar, a sophomore at Sai University in Chennai, India, majoring in Computing and Data Science. Driven by curiosity, I am passionate about learning across disciplines and love exploring new things, challenging perspectives—both mine and others’—and growing intellectually.

My academic interests span a wide spectrum as I value a multidisciplinary approach to understanding things. While my primary focus is on computer science and cognition, I am equally fascinated by economics, philosophy, finance, history, linguistics, music, psychology, and international relations. My journey into international relations led me to an enriching experience with Sherman Teichman, whose courses I had the pleasure of attending for two semesters. His mentorship broadened my perspective and deepened my appreciation for cross-disciplinary learning. Beyond academics, I have a diverse range of interests. I enjoy playing badminton and swimming, and I am an avid fan of racing and often participate in sim races. Additionally, I love watching movies and TV shows, particularly Star Trek, which explores various complex scientific and social themes.

I am grateful for the opportunity (and excited) to be part of the Trebuchet community, where I hope to contribute to meaningful initiatives. I look forward to learning from and collaborating with peers and mentors, and to making a positive impact.

Supporting Journalism that Builds Peace, Not Polarization

Amanda Ripley

Polarization is no longer just a cultural concern — it has become a structural threat to democratic societies. When public discourse loses its nuance, trust erodes, and collective problem-solving becomes more difficult. In such times, journalism plays a critical role in bridging divides. This is the core mission of Making Peace Visible (MPV).

MPV works to amplify the efforts of journalists who cover conflict with complexity and depth. These are reporters who refuse the simplicity of binary narratives and instead bring clarity to how conflicts arise — and more importantly, how they can be resolved.

Elevating Journalism That Interrupts Conflict

Daniel Sagar

American journalist Amanda Ripley has been a leading voice in understanding “high conflict” — persistent and identity-driven disputes that escalate through outrage and fear. Her work sheds light on the media’s role in either inflaming or de-escalating tensions. Through training programs and fieldwork, Ripley encourages journalists to move away from “us vs. them” narratives and to ask more constructive questions that foster civic dialogue.

In Colombia, journalist Daniel Salgar reported on the reintegration of former FARC fighters following the 2016 peace accord. His coverage moved beyond the traditional enemy-versus-hero framework and helped create space for reconciliation and inclusion. His storytelling exemplifies journalism’s capacity to support peacebuilding.

A Call to Support Peace-Focused Journalism

This July, MPV is aiming to raise $40,000 to expand its work. A 3-to-1 matching donation offer means each contribution will be tripled. Funds raised will directly support:

Journalists producing in-depth, underreported stories on peace and conflict transformation through the MPV Story Awards

Public symposia and gatherings that connect journalists with peacebuilders to reframe how stories are told

The Making Peace Visible podcast, which brings solutions-focused journalism to audiences in over 120 countries

In a time of rising division, investing in journalism that makes room for nuance and reconciliation is a step toward safeguarding democratic values.

About Making Peace Visible

Founded by Jamil Simon, MPV is a US-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to reshaping how conflict is reported. Donations are tax-deductible as allowed by law.

For more information or to contribute to MPV’s mission, visit Making Peace Visible.

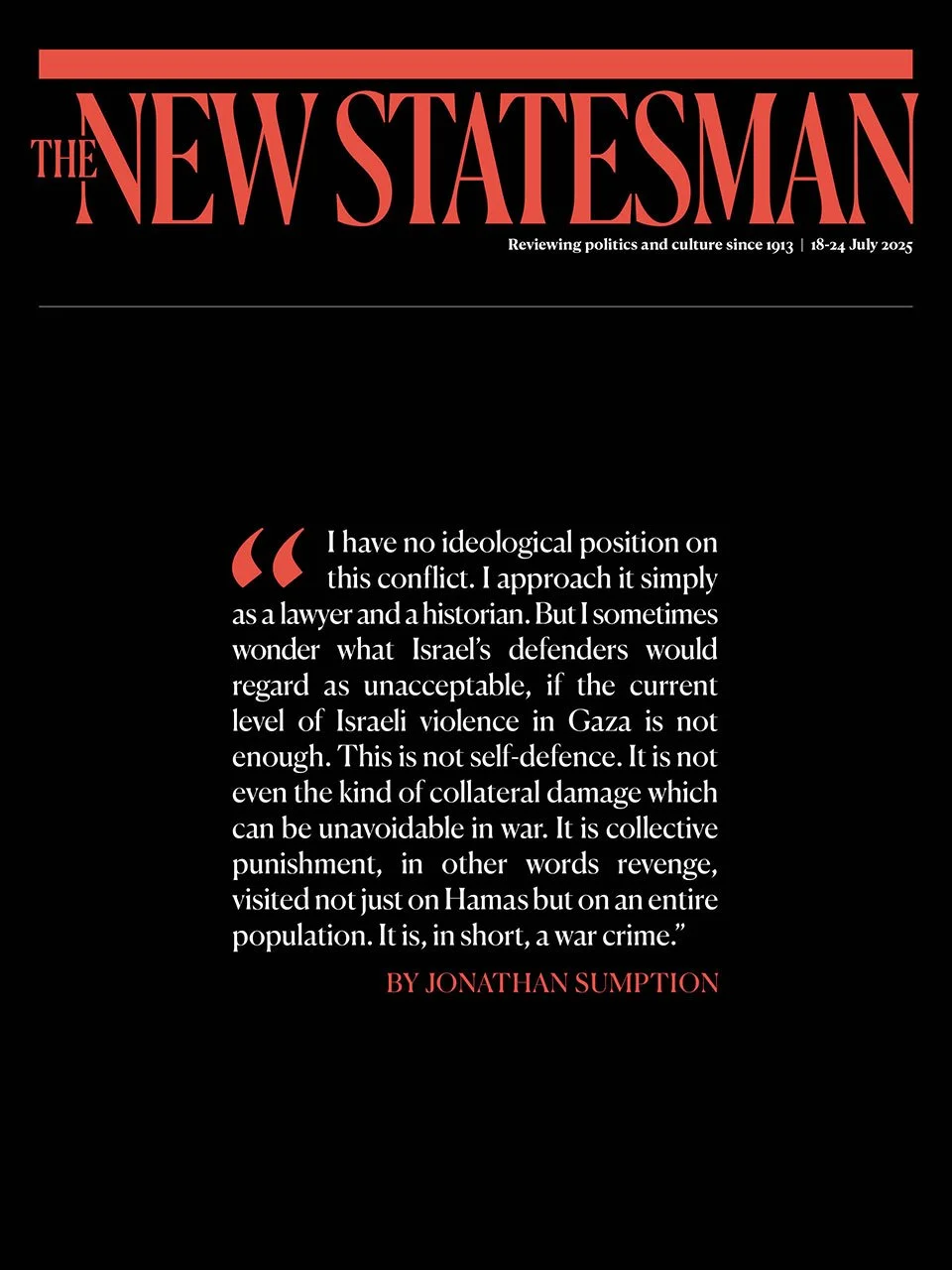

Legal and Humanitarian Reflections on the Gaza Crisis

In a recent essay published by The New Statesman, legal historian and former UK Supreme Court justice Jonathan Sumption offers a powerful critique of Israel's ongoing military actions in Gaza, situating the conflict within the frameworks of international law and humanitarian standards. Sumption states that his analysis is not driven by ideology, but by the standards of legal and historical inquiry.

He begins by highlighting that Operation "Gideon’s Chariots" — launched by Israel in May 2025 — demonstrates a pattern of collective punishment against Gaza’s civilian population. While Israel claims to be targeting Hamas, Sumption argues that the scale and manner of its military actions go far beyond proportional self-defense and amount to collective retribution.

International Law and War Crimes

Sumption outlines key provisions of international humanitarian law, particularly the Geneva Conventions, which prohibit targeting civilian infrastructure, displacing populations, and using starvation as a method of warfare. He asserts that Israeli operations in Gaza have violated several of these provisions. The destruction of hospitals, residential buildings, water systems, and the restriction of humanitarian aid are all cited as breaches of established legal norms.

He also notes that the International Criminal Court has issued arrest warrants for Israeli officials and that international bodies, including the United Nations and several Western governments, have openly criticized the conduct of the Israeli military.

Genocide and Displacement

One of the central questions in Sumption’s essay is whether Israel’s actions amount to genocide. While genocide requires the intent to destroy a group in whole or in part, Sumption points to statements made by senior Israeli officials advocating for the displacement of Palestinians as potential evidence of such intent. These, he argues, are not isolated political remarks but reflect broader government policy, including proposals to build internment camps and displace Gaza’s population to third countries.

According to Sumption, the scale of destruction — with over 57,000 Palestinian deaths reported, most of them women and children — along with deliberate restrictions on aid, signals a campaign not only against Hamas but against the civilian population as a whole.

Consequences and the Future

Sumption warns that such strategies are not only legally indefensible but strategically flawed. He suggests that even if Hamas were to be physically dismantled, its ideology — rooted in the lived experience of oppression — would endure. Lasting peace, he argues, can only be achieved through a political solution that acknowledges the rights and attachments of both Israelis and Palestinians to the land.

The article concludes by rejecting the binary framing of the conflict that equates criticism of Israeli policy with anti-Semitism. Drawing from historical examples and legal precedent, Sumption urges the international community to uphold humanitarian standards universally — whether in Gaza, Ukraine, or elsewhere.

Mid-Year Check-In for Fundraising and Social Impact Goals

As we pass the midpoint of the year, it is an ideal time for nonprofit and social impact teams to pause and conduct a strategic review of their progress. A mid-year check-in offers an opportunity to evaluate what has been accomplished so far and determine whether current strategies remain aligned with overarching goals.

Organizations are encouraged to reflect on the fundraising or corporate social impact objectives set at the beginning of the year. Key questions to guide this process include:

What initiatives or strategies have proven effective so far?

What should be scaled or emphasized further?

Are there important actions or approaches not currently in place that should be initiated?

What should be discontinued or revised based on current outcomes?

Following this review, teams should assess whether their existing goals and strategies require adjustments. This may involve redefining specific targets, reallocating resources, or revising timelines. Importantly, any updated approach should be followed by clearly defined next steps, with roles assigned and deadlines established.

Additionally, teams are encouraged to seek external input to help validate or challenge internal assumptions. This can be particularly useful when shaping new strategies or entering unfamiliar territory.

For those exploring grant funding, it is important to note that identifying potential funders is only one part of the equation. A strategic approach, coupled with the right skills, is essential for turning potential into actual funding. A free masterclass is available to provide insight into this process, offering guidance on what it truly takes to secure grants effectively. [Watch here]

Nonprofit professionals and social impact leaders seeking more guidance can subscribe to regular updates and tools, or share this information with colleagues who may benefit from a structured approach to planning and fundraising.

Social Impact Compass: www.socialimpactcompass.org